Director Takashi Yamazaki’s bold new take on the classic kaiju Godzilla has stomped its way into theaters, bringing a sobering look at post-World War II Japan that balances out what could be just another cheesy creature feature.

In the film, we meet Koichi Shikishima, a kamikaze pilot who abandons his mission in the waning days of World War II as Japan’s loss becomes certain. Following his return home to a decimated Tokyo, he is shamed by his community for his cowardice, by all except for a young woman named Noriko Oishi and her adopted daughter Akiko. The three soon become a makeshift family and find some semblance of peace, until the titular Godzilla makes his way to the shores of Kyoto, leaving a trail of destruction in his wake.

The film manages to be equally stomach-churning and awesome. Photo courtesy of Toho

One of the first things that jumps out about this film is the uneasy fact that it is a country that was part of the Axis powers reflecting on its own involvement in World War II. For a movie about a giant, fire-breathing monster, it handles the topic with a good amount of nuance, with the most direct criticism being lobbied at the Japanese government and their reckless abandon of human life.

The way American filmmakers and Japanese filmmakers handle the character of Godzilla is strikingly different. Recent American takes in Legendary Pictures’ “Monsterverse” show him as something of an ecological anti-hero, while the best Japanese films have almost always treated him like a dark reflection of humanity, which is certainly the case in “Godzilla Minus One.” Building on the themes of how Japan’s government handled World War II, the film uses the atomic monster to show the countless civilians that were put in harm’s way by the actions of the Japanese government.

The cast of characters is consistently charming and witty in lower-stakes sequences. Photo courtesy of Toho

The human drama on the whole is so compelling and moving, that it becomes easy not just to forgive, but to entirely forget that Godzilla himself does not have a lot of screen time. The lack of screen time for the big guy could be chalked up to budget, which ran at roughly $15 million, compared to the 2021 film “Godzilla vs. Kong,” which cost about $155-200 million. However, it never comes across as a budgetary issue and instead feels as though Yamazaki knows exactly how and when to make the monster its most terrifyingly effective.

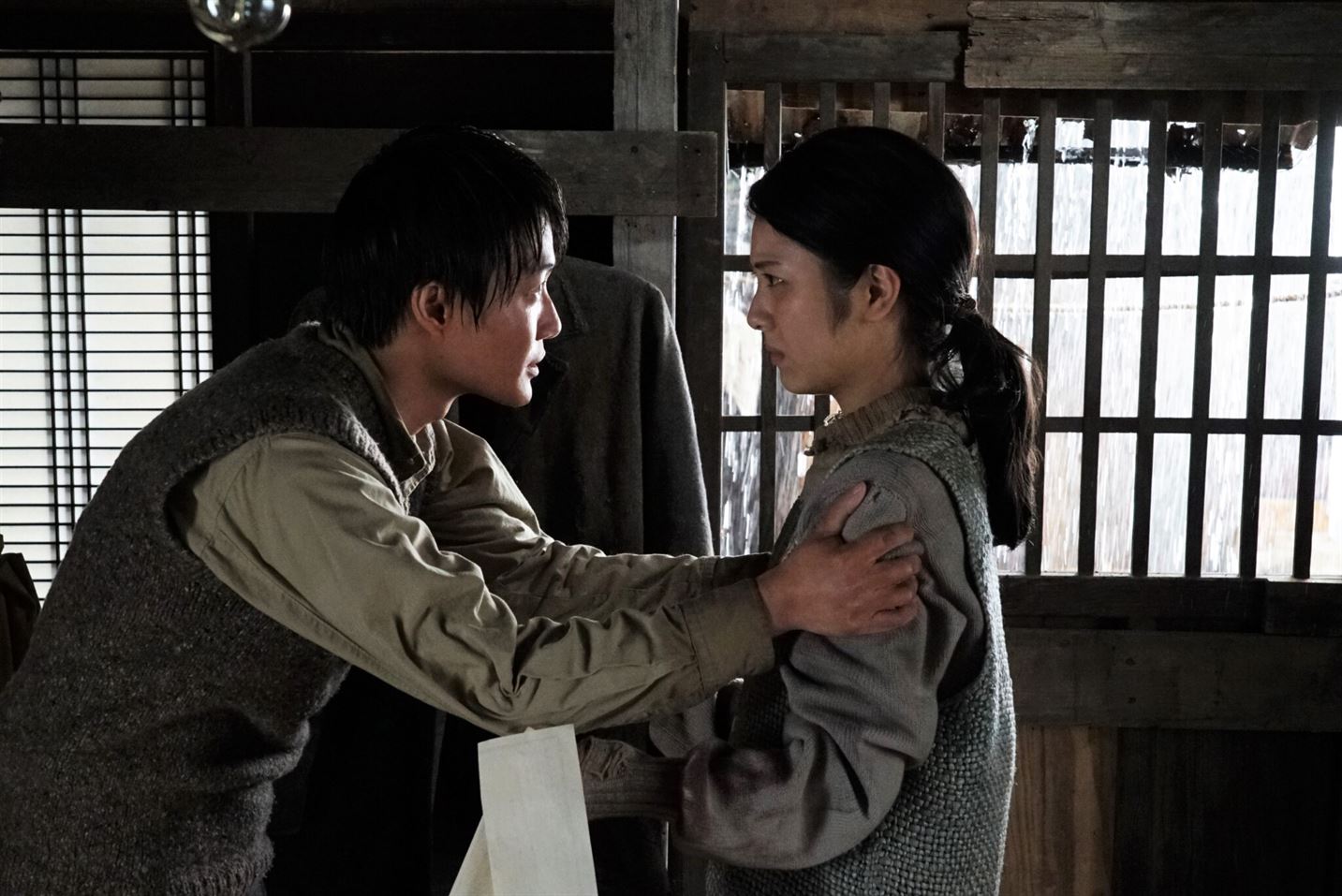

By anchoring the story in something so simple, a found family grieving a universal trauma, the film makes itself infinitely more compelling than it otherwise would be. As an audience, you find yourself not just rooting for the humans because they are the “good guys,” you root for them because you want to see this family remain intact.

The found family aspect makes the film infinitely more compelling. Photo courtesy of Toho

Even with the weight of its themes, “Godzilla Minus One” never strays too far from being a crowd-pleaser. Its central cast is consistently charming and witty in scenes where the stakes are not as high, and as horrific as the violence of Godzilla’s destruction can be, it is hard not to get a kick out of how cool the action is.

One particular moment that was equal parts stomach-churning and awesome came from the first usage of Godzilla’s iconic atomic breath; his dorsal fins began to glow a blue light and extend out of his body, before slamming back down into his spine and releasing flame, acting like the hammer of a firearm. While the outcome is horrific and emotionally devastating, there is no denying just how inventive and entertaining the buildup is.

As with the best Godzilla films, "Godzilla Minus One" treats the eponymous kaiju as a dark reflection of humanity. Photo courtesy of Toho

On the whole, “Godzilla Minus One” is one of the best Godzilla films ever made, full stop. While the American films certainly fill a niche of somnambulantly polished creature features, “Godzilla Minus One” is a more thoughtful piece that lives up to the lofty ambitions of the 1954 original. So long as you can leap over the one-inch barrier that is reading subtitles for a couple of hours, “Godzilla Minus One” is a magnificently monstrous time at the movies.