A teenage girl’s adolescent years are when she first learns how disappointing the world can be. The hope and wonder that come with childhood begin to drift away as she discovers the perceptions that are laid out before her.

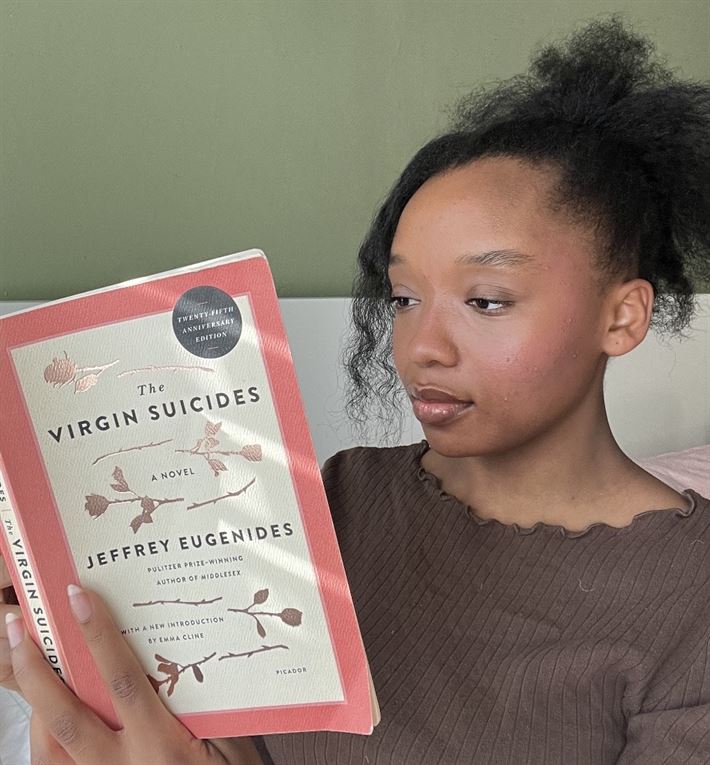

“The Virgin Suicides” by Jeffrey Eugenides tells the story of a quiet suburban neighborhood in 1970s Detroit that is hit by an unimaginable tragedy. The focus is on the Lisbon family, which includes five sisters—Lux, Cecilia, Therese, Mary and Bonnie, their strict mother and their abstracted father. In a matter of 13 months, all five sisters commit suicide.

Based on the premise, you might think that Eugenides delves into the minds of these girls to tell their stories, but he takes his own approach instead. This story is told from the perspective of the juvenile neighbor boys who watch the girls at school, at church and from across the street. At this point, they are all middle-aged adults with wives and children and they’re reflecting on their account of what happened.

Let me start by saying I had never felt so genuinely frustrated, confused and utterly annoyed while reading a book. Yet, by the time I finished, this book changed the way that I appreciate written works. I still find that it resonates with me more than anything I have ever read. It was so maddening and intelligent that I couldn’t help but think about it every day.

The overstuffing of grandiose vocabulary alone made me want to throw the book across the room a few times. The narration was tiring. I rolled my eyes when a small mention of a person or event would turn into tangents that took over most of the chapter without relevance to the story. On top of that, the author chose to include random, borderline racist comments that completely threw me off. Halfway through the book, my interest was completely gone, but a random glance back to the first chapter changed my perspective of what this book was.

This story was about teenage boys almost as much as it was about teenage girls. The random tangents focusing on even the most random detail, the distracted and unattached way of discussing the girls and practically everything that agitated me about this book were supposed to make me feel that way. The boys had no real concern or compassion for the girls. They saw them as the epitome of ideal beauty. They even found themselves disappointed when they take them to the school dance because they finally spoke to each girl for the first time, and it disrupted their fantasies. They complained about how average the girls were up close and individually.

Their parents also saw them incorrectly. Their father didn’t know how to interact with the girls and saw them as strangers. Their mother was controlling and overbearing with strict limits on television, after-school time, clothing and almost anything that could give the girls the slightest feeling of happiness and freedom. Any bit of pushback from the girls was met with unreasonable punishment, including pulling all five girls out of school after Lux came back from the dance late.

In every aspect of the Lisbon girls’ lives, they’re viewed as something to control or admire, yet ignore. This is what makes this book a reflective masterpiece. Eugenides perfectly captured each set of characters. The girls want the space to be themselves and at least learn who they are in the first place. The boys are immature and self-serving. They view the girls as perfect and view themselves as “nice boys” the girls should love, yet they had never made an effort to interact with them. Even in adulthood, they claim they were and still are in love with them. Their parents subscribe to the idea that physical presence, teaching obedience and providing basic human needs are as far as their parenthood should go. Anyone can pick up this book and find that they’ve played the role of at least one of these characters, even if it’s a hard pill to swallow. It captures incredible complexities in the midst of mundane life.