Many Latino parents decide not to give the sex education talk because they are scared they will encourage their kids to have sex, get pregnant and corrupt their religious beliefs, which state they should stay abstinent until marriage.

However, without giving sex-ed to their children, they are depriving them of important information regarding STDs, different changes their body goes through during puberty, how to practice safe sex and what consent is.

According to Pew Research, 77 percent of Latinos are Christians. A majority of them may also put their children in religious private schools where the sex education is focused on abstinence. There is no talk of what changes their body is going through or what sex actually is.

Karla Cortez, a junior business major with a concentration in business analytics, grew up in her Mexican household with no information on sex-ed. Her parents never had a sex talk of their own, and she thought it would make them feel awkward.

“[My parents] never told me because they thought I would learn,” Cortez said. “I learned from TV, which made me sad because it didn’t sound real. I also learned from friends, and in sixth grade everyone was having sex.”

Cortez was confused that her classmates in the sixth grade were having sex when she didn’t even get her period. She remembered getting a brief period talk from her two older sisters, but she only knew about pads and never understood how a tampon worked.

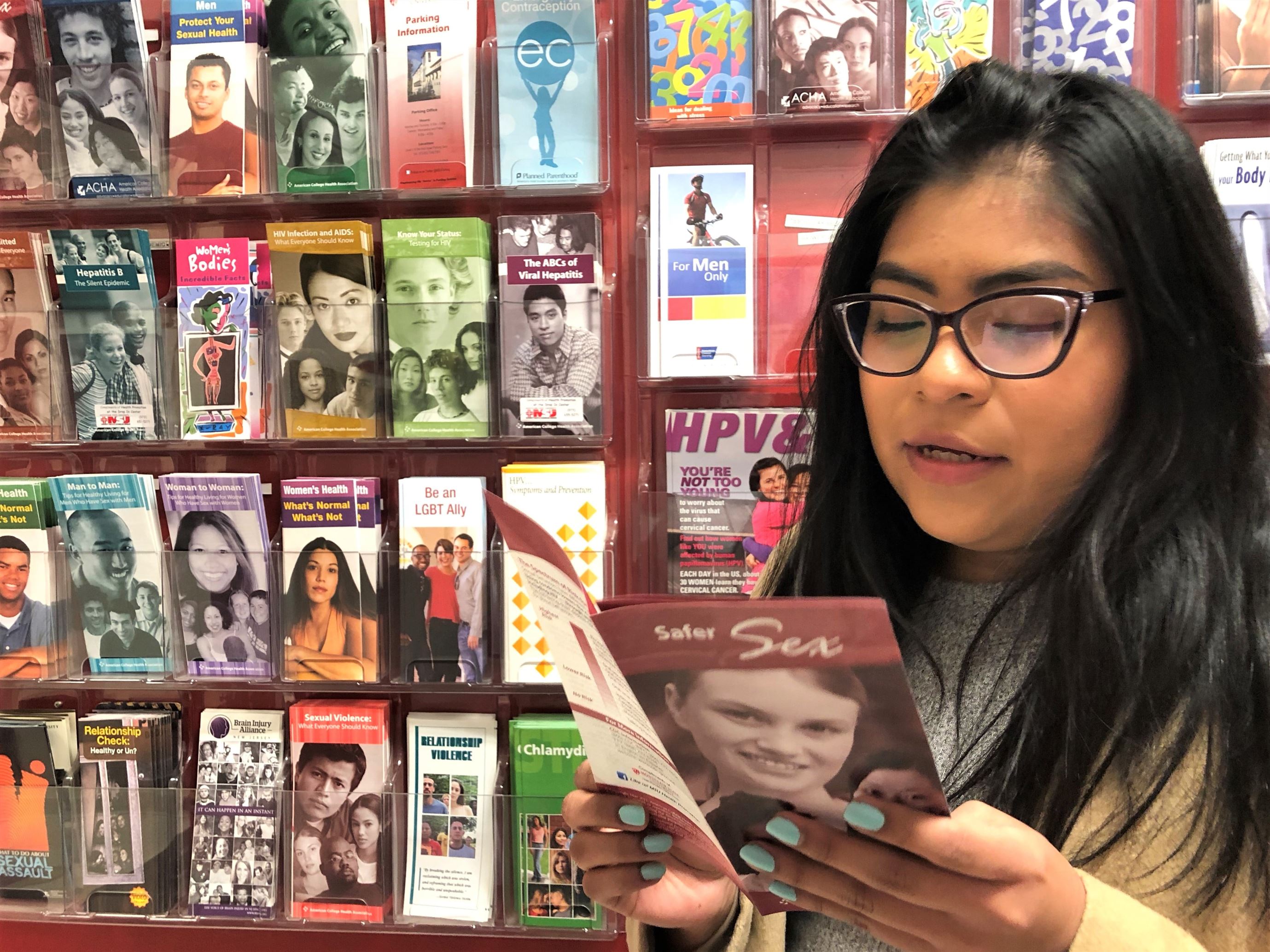

Karla Cortez reaches for a pamphlet about women’s bodies in the Health Drop-in Center at Montclair State University. Fiorella Medina | The Montclarion

She went to Catholic school all her life and her only form of sex-ed from her school was take a shower, put deodorant on and save sex for marriage. Although Cortez was able to cope, she feels that her family members were greatly affected by not receiving a sex talk.

“My family is very religious. Growing up, my cousin got knocked up and it kept happening in my family,” Cortez said. “Four of my cousins had a teen pregnancy so I feel like my parents never told me to save sex for marriage because it just kept happening.”

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, in 2017 the birthrates for Hispanic teens and non-Hispanic black teens were more than two times higher than the rate for non-Hispanic white teens.

Cortez was glad her friends would also educate her with either their own sex talks from their parents or their own experiences.

“I learned there’s an emotional part people don’t talk about, but it’s there,” Cortez said. “You have to figure yourself out first, and don’t have sex just to have sex.”

She hopes to give her 7-year-old sister sex education as soon as possible.

Samantha Soto, a junior marketing major, had a different experience with her Peruvian household teaching her about sex ed. The youngest she remembers having her mother talk to her about puberty and sex was at 7 years old.

“My mom would give me the sex talk but also wanted me to wait until I was a bit older and not rush into it,” Soto said. “She’d say, ‘Be sure who you’re going to be with you don’t have to wait ’til marriage because by the time you get to marriage you’re stuck with whatever you got.’”

When Soto’s sister came from Peru to America at 8 years old, her mother’s puberty and sex talk started to get more serious.

“When my sister was 8, she lived in Peru with her grandparents and she didn’t know about anything, then she came here,” Soto said. “My mother taught her about everything about what boys have, body parts. She’d say what boys want, what they would do to themselves, what they want from women and she would say, ‘Okay, you know this, but you might want it, too because hormones are there and you get these feelings, but you have to learn how to control them and be safe.’”

Samantha Soto (left) and her mother, Rosa Soto (right), talk about how sex education is important. Ari Lopez Wei | The Montclarion

Soto’s mother, Rosa Soto, didn’t want her daughters to go through what she went through as a young teenager.

“I had to learn from my friends,” Rosa Soto said. “My sister thought she was pregnant with a kiss and got her period super young, I didn’t want my daughters to be as afraid or unprepared as she was.”

Samantha Soto began sex ed in seventh grade, but she already knew more than what they taught her in school. All her friends were in complete shock and being immature about it. However, Soto was prepared with this knowledge being repeated to her and was happy that her other classmates were finally learning.

“A lot of them who I knew had religious families and who were too shy to talk about sex education with their children, thinking it might push them towards having sex in the future,” Soto said. “They’re the ones who actually ended up having kids at a very early age.”

Justin Marquez, a junior biology major, was raised Christian and in a Puerto Rican and Costa Rican household. He was given the sex talk accompanied with biblical aspects of love and told to wait for marriage with verses from the Bible.

“My mom was the one who said, ‘Although you should wait for marriage, if you do it at least do it with someone you love and only if they want it, too,’” Marquez said.

A variety of pamphlets are in the Health Drop-in Center at Montclair State University. Ari Lopez Wei | The Montclarion

Marquez also received sex ed in middle school and high school but believes that not everything about sex is taught there.

“It is an awkward conversation to have with your children, but I don’t think sex education at school covers it all and tells the complete truth,” Marquez said. “I think it’s important to talk to your children about it.”