Johanna Ponce can remember being dragged to a local jewelry store to transfer money to her grandmother in Mexico since before she knew how to count money herself. She would enter the dimly lit store a few times a year and stand next to glimmering necklaces and rings as her dad sent money back to his mother in Puebla. Maybe, if she was lucky, her dad would take her out to eat after they were finished.

Her father has worked at Chuck’s Cafe in Princeton, New Jersey since he first came to America in his early 20s. He does not think much of sending his mother $200 three times a year to help out and take advantage of the American dollar’s purchasing power in Mexico.

Ponce, now 21, is a child advocacy and social work major at Montclair State University. She doesn’t consider these trips to the jewelry store to be a big deal. What she doesn’t realize is that these quick trips help uphold a multi-billion dollar industry and powerful global economic structure.

Johanna Ponce sits in her apartment and describes sending money to her grandmother in Puebla, Mexico. Kristen Milburn | The Montclarion

The money transfer industry is dependent upon immigrants ducking into pharmacies, jewelry stores and grocery stores to send money to loved ones in other countries. There’s money to be made in sending money, and transfer businesses like Western Union have capitalized on it.

Instead of mailing money to someone and hoping it doesn’t get lost or stolen, customers can go to any Western Union location with cash or checks and an associate will send a 10-digit code to another Western Union located in over 200 countries. The recipient can go to the receiving Western Union and request the money be paid out to them. As the most popular transfer service, Western Unions are often found in other places of business to keep operating costs low while maximizing accessibility and ease for customers.

Bryant Flores has worked at a Western Union located within a Stop & Shop in Westfield, New Jersey for four years, doing just that. There, he helps customers send money ranging from a few dollars to $5,000.

Some of Flores’ customers have transferred money through the Western Union for years, Flores said. They come routinely, usually around payday, and send an average of $100 to other countries. While the money sent overseas might help sustain a large family or be sent to loved ones customers haven’t seen for years, the transactions are not particularly emotionally charged as customers send money quickly and easily.

Transferring money is such a normal occurrence for people that not many customers stick out to Flores. The most notable customers he has are the ones who receive money instead of sending it.

“Most people send money, not receive it,” Flores said.

While these services help individuals support families and loved ones, Western Union is, at the end of the day, a business and profits accordingly.

“The number of services and the strength of the currency in the receiving country impacts the fees we charge,” Flores said.

The average fee to send money is around eight percent, but sending to African countries puts the average fee at around 12 percent. Western Union optimizes their fees to align with the supply and demand so they can make the most money.

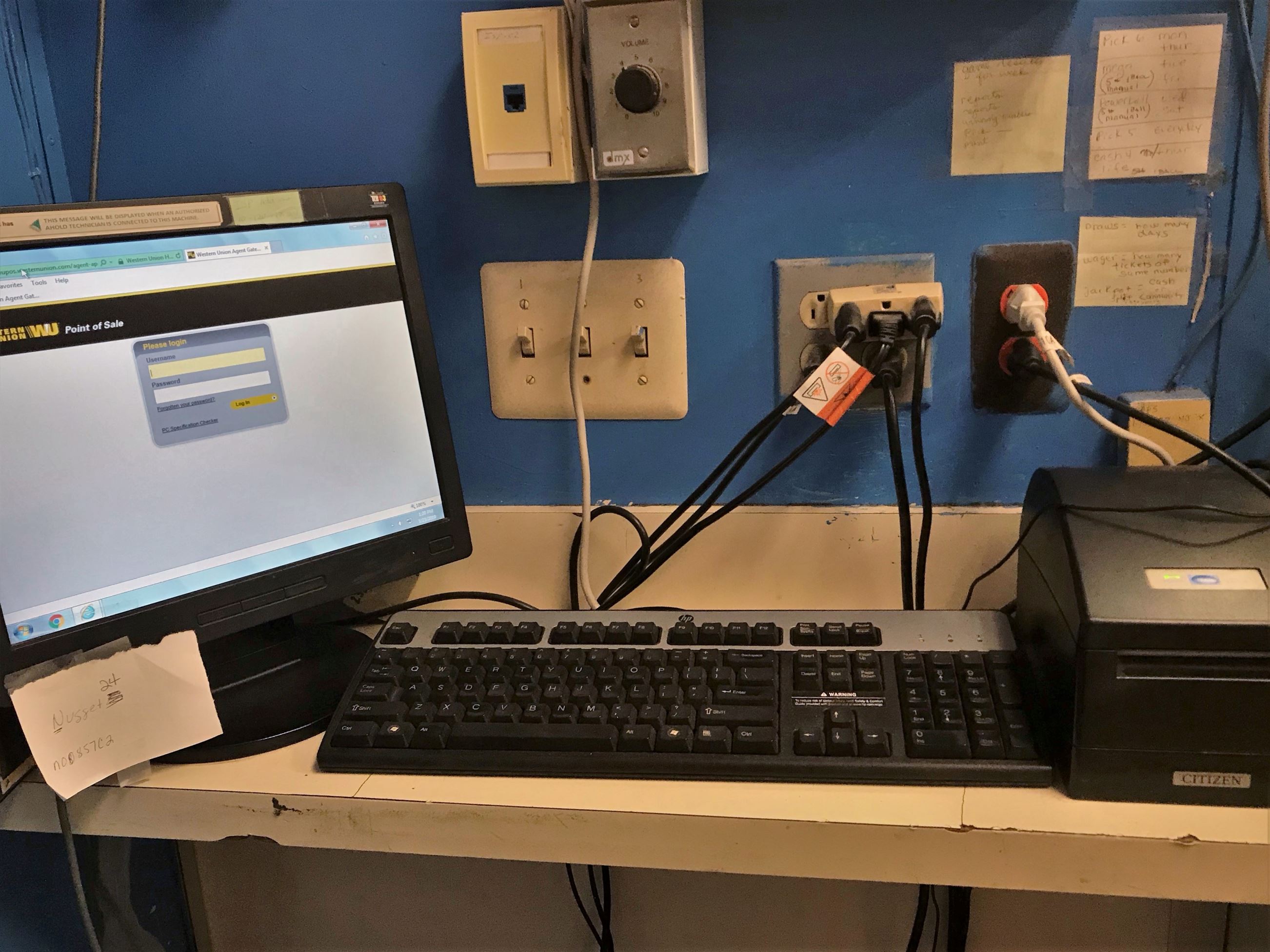

Flores’ Western Union work station is cramped but has the ability to reach other Western Union locations in over 200 countries. Photo courtesy of Bryant Flores

The Western Union business model is not the only beneficiary for people sending money across borders. Money transferring has become such a common practice that countries depend on, and account for, the remittances.

“The impact of what is being sent to other countries is still huge,” said Richard Bliss, an economics professor at Babson College. “Immigration is driven by economics. People recreate their culture here because they like it. They just need American money and safety. And countries don’t crack down on people leaving to go to other places illegally because they rely on the money being sent back.”

The money being sent back, then, is no chump change. Over $429 billion in remittances were transferred in 2016, dwarfing the $135 billion of official development aid allocated to countries around the world, according to The World Bank. A growing amount of gross domestic products (GDP) around the world are bolstered by remittances, such as in Tajikistan, where 35 percent of the GDP is money that comes in from overseas.

Western Unions, such as this one located in a Walgreens in Somerville, New Jersey, don’t require a social security number or bank account to transfer money, making it a popular money transfer service for undocumented immigrants. Kristen Milburn | The Montclarion

People often cite the cost of supporting immigrants as a reason to crack down on immigration, but Bliss argues that severely limiting immigration could have long-term and lasting economic consequences as the flow of money to other countries would decrease. Transferring money aids the individuals directly receiving money, it supports the business model Western Union and other countries have created and contributes to the delicately balanced global cash flow.

These things don’t occur to Ponce when she sends money to her grandmother. She doesn’t think of the global implications of her remittances. Instead, she focuses on her grandmother, what other errands she will run after the money is sent and what exams she has to study for when she gets back to her apartment after this routine.

“Sending money isn’t a huge deal,” Ponce said.

For millions of people, sending a few hundred dollars here and there is not a huge deal. Doing so in a Walgreens, a jewelry store or a Stop & Shop isn’t a huge deal either. But the billion-dollar industry behind the global economic force of remittances is most certainly a very huge deal.