The Montclair Art Museum houses over twelve thousand art pieces showcasing American culture, some of which represent the diverse Indigenous populations across the country.

On Sept. 13, the museum opened the “Interwoven Power: Native Knowledge / Native Art” exhibition, displaying the intricate works crafted by Indigenous women and how their respective backgrounds intermingle with the stories they wish to tell.

As the title of the exhibition suggests, the featured artists all work in mediums involving weaving fibrous materials into each other to create intricate and beautiful pieces.

Kimimila, by Kevin and Valerie Pourier, Ogala Lakota, 2008. Made from buffalo horn, inlaid with mother of pearl and lapis lazuli. Jessica Hosszu | The Montclarion Photo credit: Jessica Hosszu

At the beginning of the opening ceremony, patrons traversed the ornate works of artists hailing from around the country and witnessed how the innovation of Indigenous Americans has persisted for centuries.

The event shifted to a panel hosted by the exhibition’s curator and organizer, where three featured artists took turns to explain their creative processes, inspirations and struggles.

A timeline necklace made by Roxanne Swentzell and Rose B. Simpson, a Santa Clara Pueblo mother-daughter duo, constructed from ceramic, mud beads, and other materials. Jessica Hosszu | The Montclarion Photo credit: Jessica Hosszu

Laura J. Allen, the curator of Native American art at the museum, organized the exhibition because she wanted to emphasize the importance of these ancient practices and how crucial to the legacy of their parent tribes they are. Such an exhibition, Allen said, helps to preserve not just the physical works but also the history and legends that persist through them into the modern day.

Laura J. Allen, curator of Native American art at the Montclair Art Museum. Jessica Hosszu | The Montclarion Photo credit: Jessica Hosszu

“[The exhibition] is a metaphor, thinking about the native knowledge that is woven throughout,” Allen said. “They’re taking these practices in interesting and sometimes entirely new directions, creating new forms that are powerful expressions of legacy and sovereignty.”

Elizabeth James-Perry, 51, belongs to the Aquinnah Wampanoag tribe of Massachusetts. Her access to and knowledge of maritime resources such as quahog shells and fibrous plants like milkweed allow her to produce pieces that boast vibrant colors from rich purples to bright yellows. James-Perry is one of the most accomplished Indigenous artists in New England, her modernization of northeastern leadership medallions highlights Indigenous textile traditions with a modern flair.

Elizabeth James-Perry’s angular sun/star symbol medallion, 2022. Jessica Hozzsu | The Montclarion Photo credit: Jessica Hosszu

“Our tribal name translates to mean ‘people of the first light,'” James-Perry said. “So there’s a lot of sun symbology in our artwork, in our daily philosophy and our traditional beliefs and that comes through in even modern-day life.”

James-Perry also reminisced about growing up surrounded by women in her tribe, where she learned how to make the beaded pieces she contributed.

Sarah Sense tells about her creative process and her work history as well as family bonds that inspired her work today Photo credit: Angel Santos

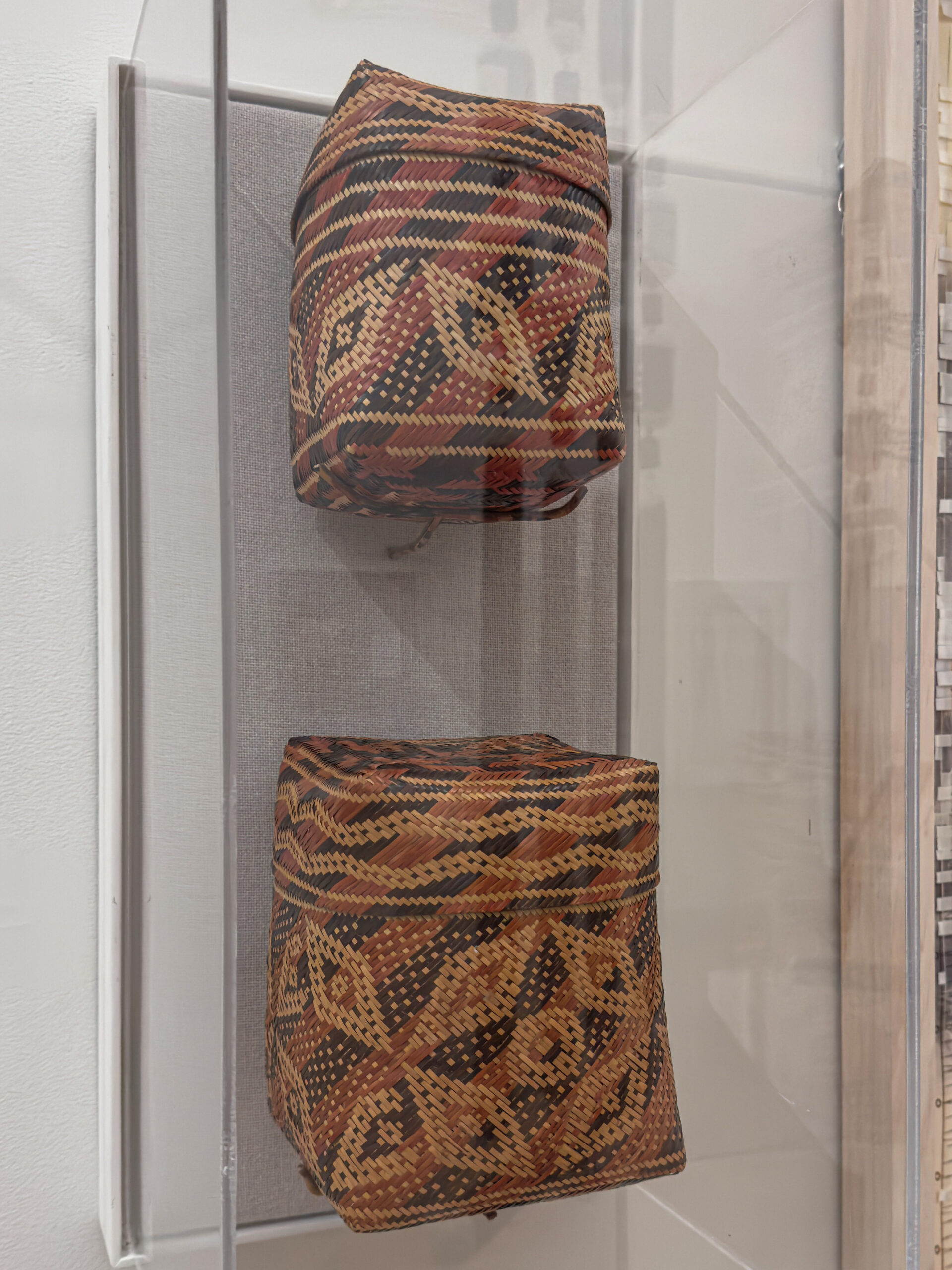

Sarah Sense, 44, comes from the Chitimacha and Choctaw tribes located in areas of Louisiana and Mississippi. She discussed her experience working on a series of pieces known as ‘Power Lines’, a series of woven pieces based on colonial-era maps, dating back to the European colonization of America. Sense sought inspiration for the title of the series from the transient nature of colonial map borders from such times.

Chitimacha woven baskets, 1911, similar to the works Sarah Sense procures. Jessica Hozzsu | The Montclarion Photo credit: Jessica Hosszu

“I was seeing a lot of maps changing borders with France claiming certain areas, English claiming other areas, Spain, of course,” Sense said. She also spoke about her time working for the British Library and studying colonial borderlines shifting over the years, but also taking into account how Indigenous populations were forced to move with them.

Sense’s work mixes photography and weaving into one, large paper images of landscapes with woven fibers stitched into them in various traditional patterns. Sense also relayed an inspiring story of sovereignty and success to the audience, how basket weaving has done far more for Indigenous populations than simply holding items within them.

Holly Wilson contributed several pieces to the exhibition and spoke at the panel. Jessica Hosszu | The Montclarion Photo credit: Jessica Hosszu

Holly Wilson, 56, a member of the Delaware nation with Cherokee roots, discussed her inspirations for her work in the exhibition, a set of vibrantly colored glass medallions sculpted from clay and then cast in glass.

![Holly Wilson’s glass medallions depicting a person [left] and a milkweed stalk [right]](https://themontclarion.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/IMG_0225-scaled.jpg)

One of Holly Wilson's glass medallion pieces. Angel Santos | The Montclarion Photo credit: Angel Santos

Describing mediums such as clay, bronze and glass as having distinct personalities reflects the appreciation she has for her heritage and tribal history. Her piece titled: “What Was, What Is, and What Will Be” explores the transience of life and acknowledges that one cannot move forward without understanding the past.

“My work is always based on stories that I’ve created,” Wilson said. “Some have connections to my culture, but it’s on just a very small level. I never want to recreate a story of a thing, because, to me, there, you don’t want to cross those lines.”

![Holly Wilson’s glass medallions depicting a person [left] and a milkweed stalk [right]](https://themontclarion.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/IMG_0226-scaled.jpg)

One of Holly Wilson’s glass medallions depicts a milkweed stalk. Angel Santos | The Montclarion Photo credit: Angel Santos

Wilson also values the educational value of her works on younger generations. “When I’ve had work up in shows, one of my favorite things is a lot of the places bring through all the [elementary school students] and what they see is themselves in a lot of the work,” the artist said.

Allison Perez, an anthropology student at MSU, interned at the Montclair Art Museum and enjoyed seeing the Interwoven Power exhibition come to fruition. Jessica Hosszu | The Montclarion Photo credit: Jessica Hosszu

Allison Perez, an anthropology major at Montclair State University, interned at the Montclair Art Museum and helped organize the Interwoven Power exhibition.

“[At the Montclair Art Museum], I got to see the pieces, take notes with native collaborators, and overall, just have a fun time just getting to see this exhibition come to life with behind-the-scenes work, which was really fun,” Perez said.