When Sergeant 1st Class Scott R. Smith was killed in 2006 in Iraq by an improvised explosive device, Garilynn Smith, the Sgt.’s widow and a current senior jurisprudence major at Montclair State University, was overwhelmed with grief, as any military widow would be. Gold Star families give the ultimate sacrifice and they are viewed with great respect and dignity.

Sgt. 1st Class Scott R. Smith was killed in 2006 while deployed in Iraq.

Photo courtesy of Garilynn Smith

But when Garilynn Smith started looking into what happened with her husband’s remains the next year, she was treated with anything but respect and dignity in the next 15-year process that unfolded.

When Smith finally got the answers she was looking for, what she found was truly shocking and abhorrent. After her husband was cremated, his partial remains were sent to a landfill in Virginia, grouped with medical waste.

The remains of soldiers who were killed in action must be dealt with respectfully. A Department of Defense directive even orders it. But that would suggest spreading ashes out at sea or Arlington National Cemetery or sending them back home with the next-of-kin if possible. But mixing American heroes along with trash is anything but respectful.

The memorial case for Sgt. 1st Class Smith, showing his medals and badges.

Photo courtesy of Garilynn Smith

She was first told this information through a phone call with the military mortuary in Dover, Delaware a year or two after her husband’s death after much effort was spent trying to get answers. At first, she didn’t believe it.

“[The man on the phone] cut me off again and said, ‘No one wanted your husband, so he was cremated with the rest of the medical waste from the hospital and thrown in the trash,’” Smith said. “So that was my initial information that I found out. I obviously didn’t believe that. I thought the guy was just being rude and I thought he was pissed off.”

Garilynn Smith is a senior jurisprudence major and a Gold Star widow of 15 years.

Photo courtesy of Garilynn Smith

But when she continued to ask questions, she eventually realized that the man on the phone hadn’t been lying. A few years later in 2011, after more digging around, she received an informal letter from one of the managers of the Dover mortuary confirming that her husband’s remains were sent to a landfill in Virginia.

At the end of the letter, it read: “I hope this information brings some comfort to you during your time of loss.” It did not for Smith. And to add insult to injury, the letter had the wrong first name of Smith’s husband and the wrong date, with the year 2008 instead of 2011.

Outraged, Smith went to a representative near where she lived, Congressman Rush Holt Jr., and told him what was going on. Once they started to ask more questions, they found out that the partial remains of at least 274 confirmed fallen soldiers, and possibly more had been treated the same way as Smith’s husband’s.

Smith then shared this information with The Washington Post once other whistleblowers came forward about other mishandlings of fallen service members. The Post published an article exposing the situation on Nov. 9, 2011.

At the same time, Smith was also a civilian Army employee. After a brief time working for the Navy civilian service, a job opened up at her former Army arsenal in 2012 that Smith was interested in. A co-worker told her about the position, so she applied.

However, it was well-known among the higher-ups at the Picatinny Arsenal she was working at in New Jersey that she was looking into what happened to her husband’s remains. She had shared her story with The Washington Post who then exposed the Army. She was a whistleblower.

First, the job application closed. Smith had a funny feeling about what was going on, but she applied again when the job application reopened.

She still didn’t get the job. Smith was on the top list of candidates both times she applied, but she was passed up for an applicant who had forgotten to attach certain documents the first time.

Smith challenged the decision, saying that the Army had violated a law that prohibited discriminating against whistleblowers. But she got nowhere. After over two and a half years, the investigation by the Office of Special Counsel ended. It was then that she decided to go to court in 2015.

At first, she fought the battle alone, without a lawyer. That’s where Graig Corveleyn, a lawyer working for Smith on other legal matters, came in.

Smith had told Corveleyn that the case probably wouldn’t get that far, that the Army would probably settle.

“I thought, ‘Okay, [this will] be a way to keep client contact and maybe get something in and quickly completed,’’’ Corveleyn said. “Little did I know that seven years later, I would still be dealing with this case.”

The first hearing for the case took place in October 2016. Seven months later, the administrative law judge gave his ruling: the Department of the Army had violated whistleblower protection law when they had passed over Smith back in 2012. As a result, the judge ordered the Army to give Smith the position she had applied for, as well as back pay.

However, the Department of the Army appealed this ruling. The department claimed the judge “was sympathetic” and “considered hearsay evidence” in his ruling. It wasn’t quite over for Smith just yet.

In fact, it wasn’t over until five years later. The administrative court that had jurisdiction over this matter, the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB), is typically made up of three members and needs at least two to make legal decisions. From the time of the appeal to just before it was decided in April 2022, there were either one or no members on the board.

Why? The President appoints members to the board as they do to any other court, and the Senate must approve them. But no matter how many judges, both former President Donald Trump and President Joe Biden nominated, none were ever called to a vote on the Senate floor.

That was from January 2017 to March 2022. Smith had been passed up for the job 10 years ago. She had found out the news about her husband’s remains 11 years ago and had lost her husband almost 16 years ago.

“How much more time of my life are they going to tie up and are they going to take from me?” Smith said. “Because I feel like 15 years of my life [have] been robbed fighting these battles. I’m 42. I’ve given up my career. I’m starting completely over again.”

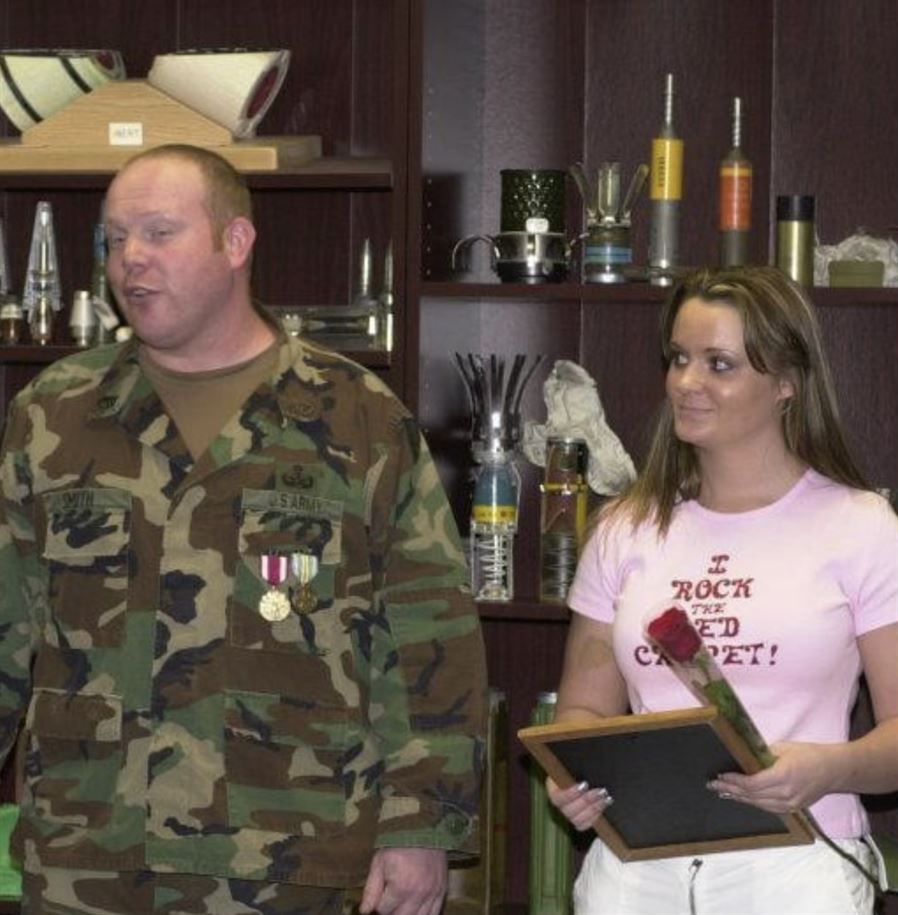

Garilynn Smith (right) spent years trying to find out what happened with the remains of her husband, Sgt. 1st Class Scott R. Smith (left), and ended up in a years-long legal battle because of what she uncovered.

Photo courtesy of Garilynn Smith

However, on March 1, 2022, two appointees were confirmed by the Senate. A month and a half later, on April 17, they denied the department’s appeal and decided on Smith’s side once again.

When Corevleyn texted her about the decisions, Smith was overwhelmed with relief.

“I just broke down,” Smith said. “‘I was just like ‘finally.’ For 15 years of grief built up in one moment to come out in 28 pages. [The judges] summarized my entire 15 years in 28 simple pages.”

Smith and Corevelyn were so overjoyed at first that they didn’t realize something else. Their case wasn’t just like any case; it was precedential, which means it will be used as a basis for similar cases in the future.

“I think that the reason that it was made precedential was [that] the court was concerned with the upper-level stuff, with the whistleblower stuff, “Is she a whistleblower?’” Corevelyn said. “‘And if she is a whistleblower, did she experience this prohibited personnel practice?’”

The Department of the Army has 60 days since the court decision to appeal again, but Smith and Corveleyn don’t expect this to happen. Instead, Smith is focused on graduating with her bachelor’s degree this year and then moving on to law school, inspired by her own case. She hopes that this case can mean something to other whistleblowers as well.

“I’m very proud of this case obviously, but I feel like all of this work was worth it,” Smith said. “And I hope that this is the case that will show other people that they can make a difference, just one voice can encourage people to come forward and cancel bad management.”