Deena Mahmoud wakes up every day at 7:45 a.m. She brushes her teeth and starts on her simple makeup look, blotting foundation around her nose piercing. On this day, she selects a black sweater, skinny jeans and ballet flats to wear to school.

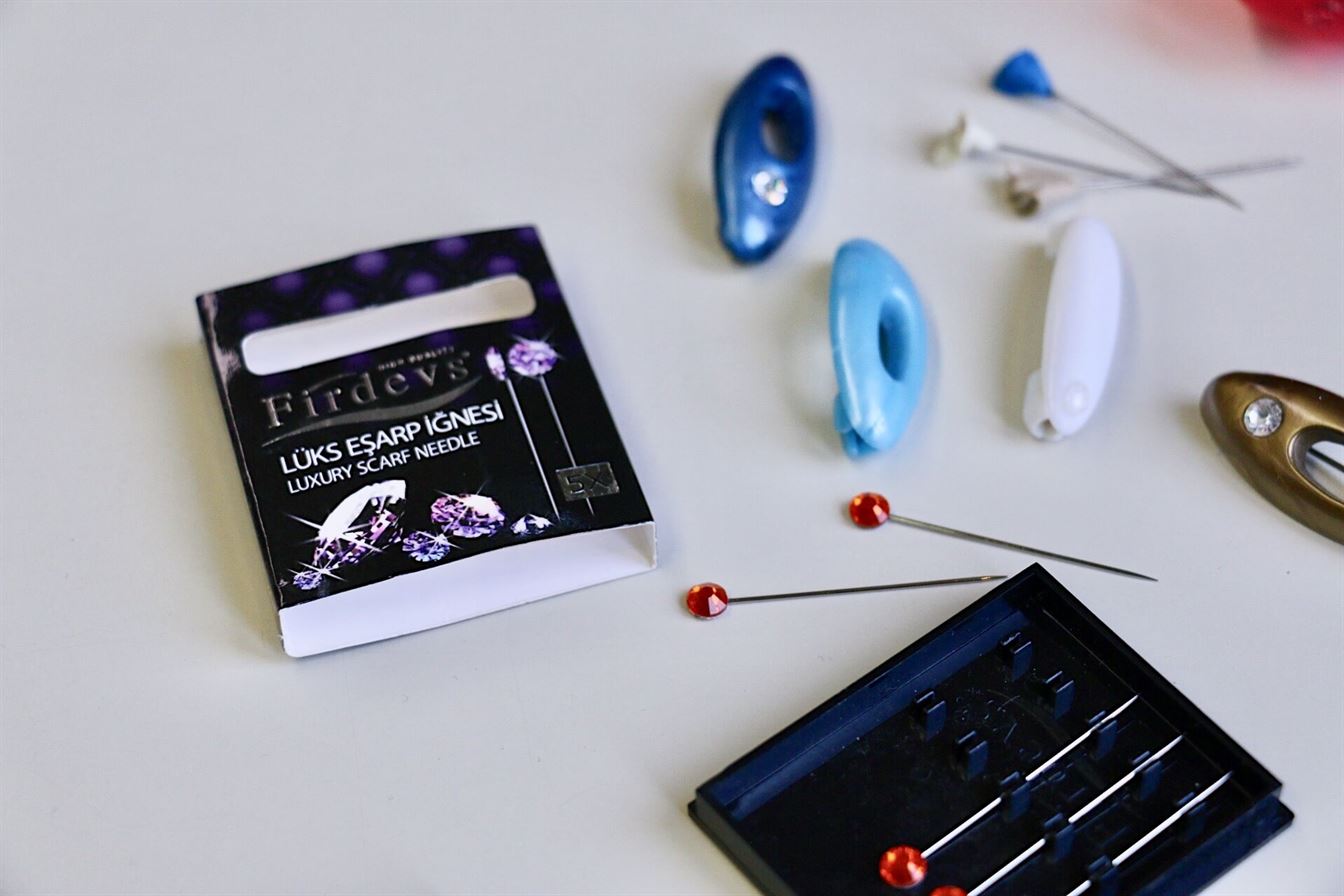

Deena Mahmoud examines the various pins she uses to secure her scarf.

Olivia Kearns | The Montclarion

Mahmoud saves the most important part of her morning routine for last: ironing and wrapping her hijab. From the scarf-filled hanger on the back of her closet door, Mahmoud debates which color and pattern will best go with her outfit before settling on a neutral tone with a thicker material. She doesn’t like the way thin silky scarves slide off easily when trying to wrap them, and she’s not a fan of stretchy jersey material either.

She secures her hair in a low bun, then puts on her umta, or underscarf. After delicately ironing her scarf in her laundry room to flatten out wrinkles, Mahmoud, who prefers to cover her hair completely, wraps her hijab around her head. It’s not the $30 Habiba Da Silva scarf she’s been eyeing online, but it’ll do.

After she selects her style – the end of the scarf hangs down in the front, so she must flip it over her shoulder like hair – Mahmoud secures the scarf with thin pins on the top and in the front.

“These are my favorite,” said Mahmoud, picking up a box of fine, jeweled pins. “They’re straight pins, and they’re very thin. Thicker pins tug on your scarf and a string might come out.”

Mahmoud uses different pin sizes to secure her hijab, but she prefers the thin Firdevs pins.

Olivia Kearns | The Montclarion

The 21-year-old Montclair State University junior studying English in the teacher’s education program is very familiar with scarves, pins and the various styles in which they’re worn all over the world, particularly because she’s been wearing the hijab for almost seven years.

The hijab is a scarf worn to cover the hair of a Muslim woman as an homage to God and to show modesty. It is encouraged in the Islamic faith for girls to start wearing the hijab once she hits puberty, but the decision and the reasoning behind it are ultimately up to each individual girl. For Mahmoud, her choice was based on her values and connection with God.

“Some people approach me and they’re very proper. They think I’m like super religious, like they have to be careful with their words,” Mahmoud said. “But it’s like, I don’t feel like my hijab – personally for me — it doesn’t measure how religious I am. It’s more spiritual in a way. It became a part of me.”

According to admissions, Montclair State doesn’t ask about religion on their undergraduate applications. However, the school has a visibly noticeable population of Muslim women on campus who wear the hijab. Students are bound to see hijabi women while they bustle around campus rushing to class. Yet, few students see the discrimination these women face all for honoring their beliefs and showing their love for God.

Recent headlines describing women having their hijabs snatched off or videos depicting people screaming at hijabi women suggest this phenomenon is something new. Actions like President Donald Trump’s executive order last year, that halted immigration into the U.S. from Muslim-majority countries, further the narrative that this political climate is to blame for the resurrection of hateful comments and openly prejudiced behavior.

However, for hijabi women, these occurrences have always been a part of their lives.

For Mahmoud, growing up in the diverse town of Teaneck, New Jersey, her community always supported her decision to don the hijab. Aside from the occasional prejudiced referee at a high school soccer game, Mahmoud has constantly felt safe and respected in her hometown.

Outside of Teaneck’s close-knit community, however, not so kind individuals worm their way into Mahmoud’s life.

“I used to walk out and really forget about it like I would forget that I’m wearing this [hijab],” Mahmoud said. “It’s almost as if you’re wearing a cardigan or scarf around your neck. When you leave your house, you don’t think about the clothes you’re wearing. But in this political climate, sometimes I feel it, like I feel it on my head. I’m aware that I am wearing this.”

Mahmoud has faced dirty looks and terrorist comments whispered behind her back during English classes. She has been taunted with chants of “Trump 2016.” She has dealt with teachers exaggerating her last name, adding more phlegm to “Mahmoud” than she prefers.

A truly terrifying moment occurred when she was driving out of Starbucks on her way to a close friend’s house and was followed the whole way by an older white man in a sleek black car.

“I felt so guilty because I was like, ‘I shouldn’t have went to her house,’” Mahmoud said. “This guy now knows Muslim people live here.”

Canan Kumas, a 2017 Montclair State graduate with a political science degree, can relate to Mahmoud’s discriminatory and uncomfortable experiences.

The 23-year-old student from Washington Township, New Jersey, spontaneously decided to start wearing the hijab during a trip to Turkey with her mother and aunt in 2007. After asking a Turkish scarf store employee to wrap her in the hijab, Kumas’ on-a-whim decision created a new part of her.

However, Kumas was tested with an experience in the summer of 2011. While working as a cashier at her father’s diner in Delaware, Kumas was approached by a father-son duo after their meal that affected her perspective.

“I asked them if they enjoyed their meal and service, and the father said, ‘Yes, I enjoyed everything except for one thing,’” Kumas said. “I asked him if there was anything I could help with, and he pointed at my head.”

After confusion settled across her face, the man clarified to Kumas that he was unhappy with her hijab and proceeded to use racial slurs against her as well as call her a terrorist.

“The hijab has become a part of my lifestyle and it makes me feel strong-willed,” Kumas said.

Sana Mirza is an environmental Ph.D. student at Montclair State University, who wears the hijab as well as the niqab, a face veil.

Danielle Weidner | The Montclarion

Sana Mirza, a 30-year-old New Jersey native and Montclair State environmental science Ph.D. student, may be quiet but is strong. She’s dealt with discriminatory behavior since she was 12 years old when she started wearing a hijab and later at 16, after adding the niqab, a face veil.

“The hijab wasn’t enough for us in a spiritual sense, and we kind of wanted to do something more,” Mirza said “Why can’t we do something that’s allowed in our religion, to do something that’s a little bit more than what we’ve been doing for years?”

Mirza, a teacher’s assistant in the environmental science department, helps a student with a lab in a marine science class.

Olivia Kearns | The Montclarion

As a teacher’s assistant, Mirza is used to being in front of classrooms of students at Montclair State and describes herself as “lucky” for not having faced backlash here for her hijab or niqab. However, she does remember a change in attitude toward hijabi Muslim women back when 9/11 occurred.

“I felt the most change after 9/11,” Mirza said. “That was the biggest shift in perceptions and attention, for sure. It calmed down for a little bit and then it came back up when ISIS started making headlines.”

Mirza, an environmental science teacher’s assistant, wears the niqab, a face veil, as she oversees a lab that three students work on in a marine science class.

Olivia Kearns | The Montclarion

Mirza describes the resurgence of terrorist comments echoing at her down the street after these political headlines. She remembers her friends who she knew for years wondering if she was really a part of a religion that claims “the more people you kill, the higher the chance you go to heaven.”

“They were hearing about it in the news and they were just confused,” Mirza said. “All of a sudden there was an interest in, ‘Well, what do you follow? What is this?’”

While some might not understand the faith, Mirza knows what it stands for and values it as a “self-discipline.”

“Islam is really a way of life,” Mirza said. “A lot of people can have a lot of different logical reasons, like [the hijab’s] a protection, we’re privatizing our sexuality. But in the end, I think it comes down to our relationship with God and what we believe came down from him.”

Mirza poses at the amphitheater on Montclair State University’s campus.

Danielle Weidner | The Montclarion

These women try not to let comments affect them. Mirza explains how she has become so used to them that they barely bother her anymore, and Mahmoud tries to focus more on the accepting people in the world as opposed to the dividing ones.

“It’s interesting how the hijab became such a big thing,” Mahmoud said, “but it all began with just a scarf and covering your head and trying to be modest.”