If one comes from a mixed background or a migrant one that is really unknown to them, it is easy to just deem oneself a genuine – westernized to perfection – American. However, this does not properly pay tribute to those who struggled and left so much behind in the hopes of offering their kin, aka you, a chance at a better life. Something that many give up when they immigrate to the United States is their native tongue.

Like many, I have often felt on the outskirts of any particular cultural group due to a lack of language outside of English. Growing up with an extended family that is several generations deep in bilingualism, not knowing how to speak Spanish has always made me feel inherently less Hispanic and often times illegitimate.

I am often asked the questions “What are you?” and “Where is your family from?” As someone who is multicultural and/or mixed race, this is a loaded question.

Though I remember growing up with my great-uncle Pedro always asking my mother, “Have you taught these kids Spanish yet? Who will I talk to in a few generations?” I was always confused because to my knowledge at the time, my own mother, a mix that includes Puerto Rican and Portuguese, didn’t even speak Spanish or any language other than English.

https://twitter.com/babee_garcia/status/1113610929856569344

It was only later in my life, after conversations with my mother and studying cultural anthropology, that I began to understand that for a long time, bilingualism and the American dream didn’t coincide. This caused many families who immigrated to the U.S. to lose the language of their birthplace in the hopes of adopting a new home, and in turn its language, in order to attain a better life with less resistance.

My nana, maidenly Ilene Perry, is the perfect example of this. Growing up with a parent from Puerto Rico and one that was first generation from Portugal in the ‘40s put her in a position of difference from her peers. Like many born in the states with fresh immigration ties, she was taught English in school. However, she only spoke Spanish and Portuguese at home.

While her trilingualism allowed her to be closer to her roots, it put her at a disadvantage in the country of her own birth. This came to a climax when her father passed away suddenly at the hands of a drunk driver. As a result, she and her younger brother were sent to stay with an American family temporarily.

After the passing of her father, Ilene Perry refused to speak Spanish or Portuguese.

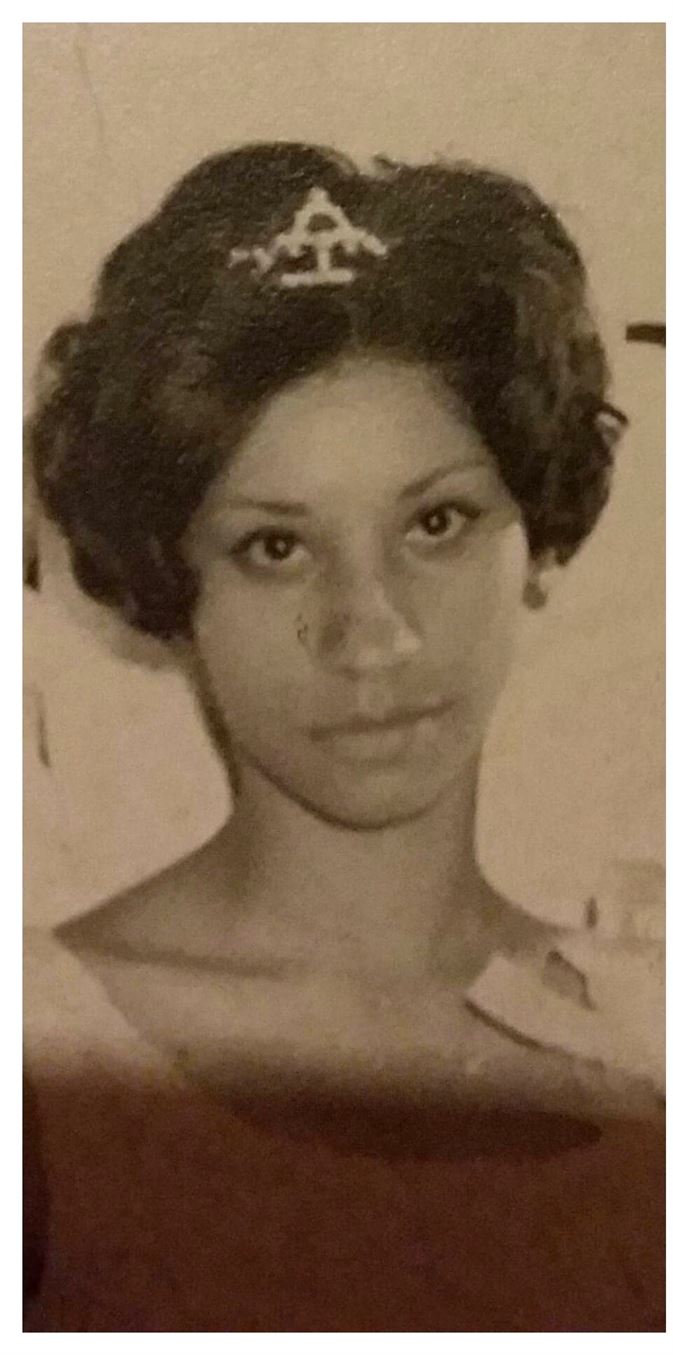

Photo courtesy of Yolanda Evans

During this very difficult time in her childhood, her grief was heavily shadowed by her inability to communicate with those who had taken her in. With her lack of fluency in English, she couldn’t even ask for a glass of water.

While being pulled by two cultures and in turn their languages, neither of which being English, she struggled to find footing within her own American experience. As a result of this, to this day she refuses to speak Spanish or Portuguese. When it came to raising her own children, my mother and my aunt Valerie, who I refer to as Titi, the same rules applied.

To my grandmother, not being able to speak English made her displaced in the place of her birth. Her immigrant ties made her have to go the extra mile and work very hard to achieve success.

Fast forward to my mother’s generation, one filled with trips to the hairdresser, dance lessons and Disney vacations. She was raised by a single mother who worked and went to college at night as a means of achieving the American dream to be successful and have a better life. During this time, it was through my mother’s grandmother that she was exposed to the Spanish language and grew up with excellent reception skills.

Ilene Perry, now Ilene Ingram, sits with her younger brother, Avelino Perry, in Queens, New York.

Dominique Evans | The Montclarion

It is unfortunate to say that the buck stopped before auditory skills in the language were fully developed. Other people in my family, including my grandmother’s younger siblings, took on the challenge of being multilingual. In an America that is more accepting of the differences among its peoples, there is far more room for people to be proud of their heritage and immigrant ties.

Even though I come from a generation in my family that not only cannot read a real map but is also not bilingual, it doesn’t stop me from realizing that even that was a sacrifice made by past generations in an attempt to offer me more opportunities and give me the chance to be on an equal playing field with those around me in achieving my own American dream.

Next time you’re on the verge of proclaiming your “American” heritage, do not forget about those who might have stripped themselves of their roots to give you that privilege.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bv5ZEi3nhTH/