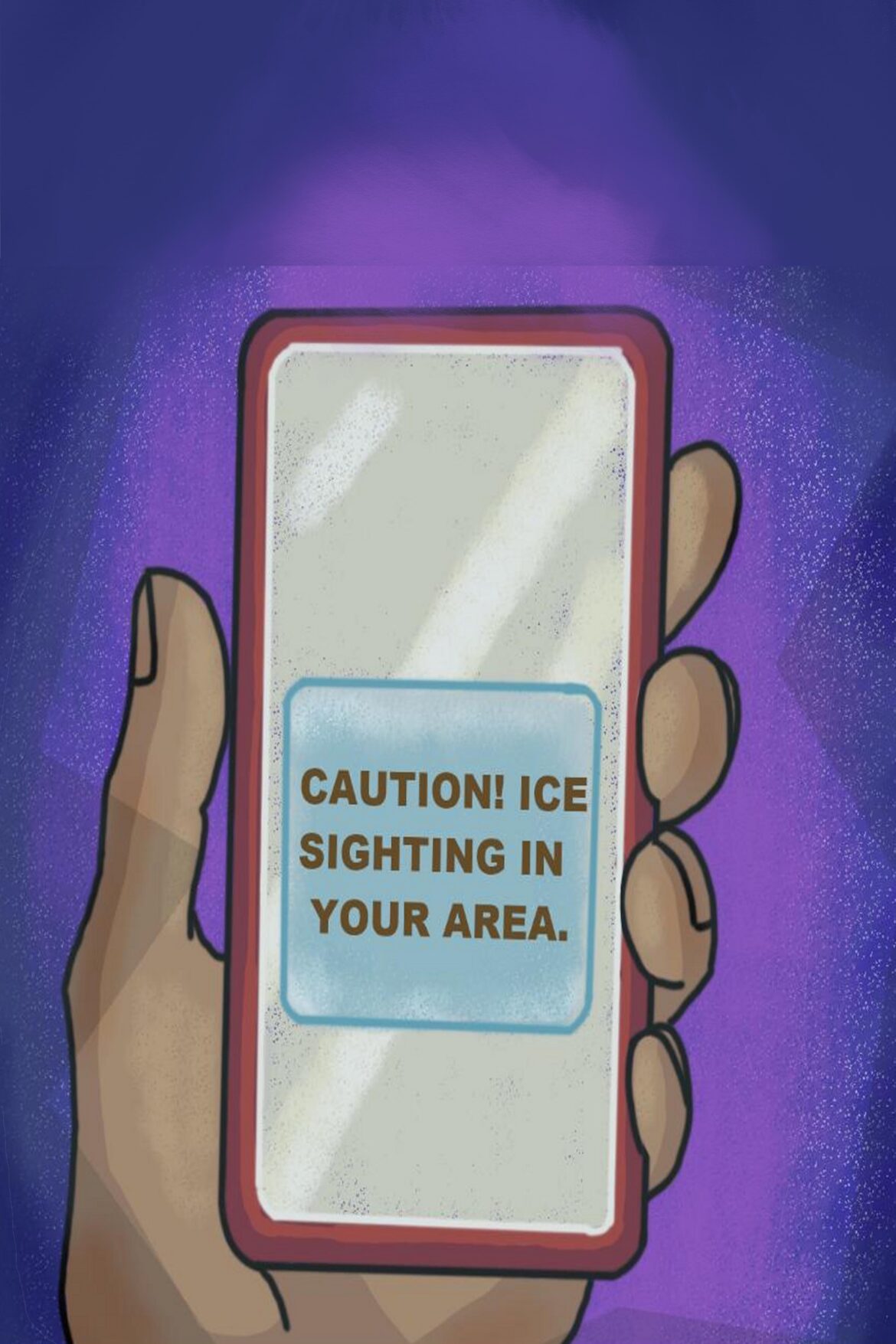

Illustration by Emma Raughley

ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) tracking apps have been popping up in the wake of dramatic changes and increases in immigration enforcement. These apps, often uploaded onto the Apple App Store, are similar to the anonymous crowdsourcing portions of map apps to inform fellow drivers of speed traps, construction, car collisions and objects on the road.

However, ICE tracking apps are focused solely on crowdsourcing information on the locations, appearances and vehicles of nearby ICE agents.

On the website of one of the more well-known ones, ICEBlock, the app’s purpose is said to be to “protect our neighbors from the terror this administration continues to rain down on the people of this nation.”

Why would an app be created to defend undocumented immigrants?

Well, it may be because the Trump administration vowed to deport 1 million illegal migrants annually. This vow was doubled down on with the increase of ICE’s annual budget and the addition of 10,000 new staff to the department.

But the pressure to perform has been forced onto ICE agents according to NBC News. This has led them to widen their range of detainees and perform several “rapid smash-and-grab operations” to hit the quotas they’ve been assigned according to CPR News. Alarmingly, this violence seems to be doled out with a heavy bias, ICE agents allegedly factoring in race when they conduct arrests.

In taking a stance on this, we turn to the words of the Associate Justice of the Supreme Court, Justice Sonia Sotomayor: “We should not have to live in a country where the government can seize anyone who looks Latino, speaks Spanish and appears to work a low-wage job.” This is now the ill-fated reality in many cities throughout the US.

The agenda of the immigration department has become more aggressive as it essentially profiles all non-White groups. There have been several instances of ICE Agents arresting and detaining Native Americans or American Citizens.

And it is not just the profiling that is problematic, but also the detainees’ treatment (or lack thereof).

Noticias Telemundo reported in January that a Puerto Rican family was detained for speaking Spanish while grocery shopping in Wisconsin. The family was not given any opportunity to speak throughout the process, violating a standard procedure. They were not released until an English-speaking family member came to show documentation and explain that the family was all native Puerto Ricans and therefore American citizens.

When the problem is unjust, people resort to maneuvering around it. This is where tools like a tracking app come in.

Many migrant workers with legal paperwork report the fear of running into ICE agents and more unsettlingly, being unable to speak about their rights as citizens. In a piece with CBS News, a Venezuelan migrant worker who is in the U.S under temporary legal status said that using the ICE Tracking app, Coqui, allows him to do his job with “a little less fear.”

For those stressed about possibly losing what they have worked hard for, these apps are a liferaft in a storm of uncertainty during this current administration. Is there any question as to why they exist and if we should oppose them?

Todd Lyons, the Acting Director of ICE, stands in opposition to this resource. Responding to a CNN article about ICE tracking apps, he said that the app ICEBlock “basically paints a target on federal law enforcement officers’ backs.” Yet many migrants attest to the same. These apps exist so that they can avoid having a target painted on their back, which always leads to dangerous situations.

Later, Lyons claimed that “ICE officers have seen a staggering 413 percent increase in assaults against them.” We should question why that is.

It has been shown that ICE agents conduct arrests and raids “wearing masks” and “without identifying themselves”. Some assaults against ICE might be because bystanders are confused, stepping in to help those they perceive as victims of an attack or kidnapping. And this, in the context of the profiling process and its goals, is essentially what is happening.

While we wait for Governor Sherrill to ban the use of face coverings by ICE agents, we must act now with what we have. With 2,376,424 foreign-born residents in New Jersey, the likelihood is virtually certain: every New Jerseyan lives near someone who is or will be affected by overstepping, unethical and dangerous actions from ICE, regardless of their legal status.

ICE tracking apps are community tools to keep our fellow human beings safe in a political climate that unjustly targets people with no reason or regard for their individual actions. With that understanding in mind, are we really going to sit around and allow this excessive violence towards 25 percent of our population to go on unreported?