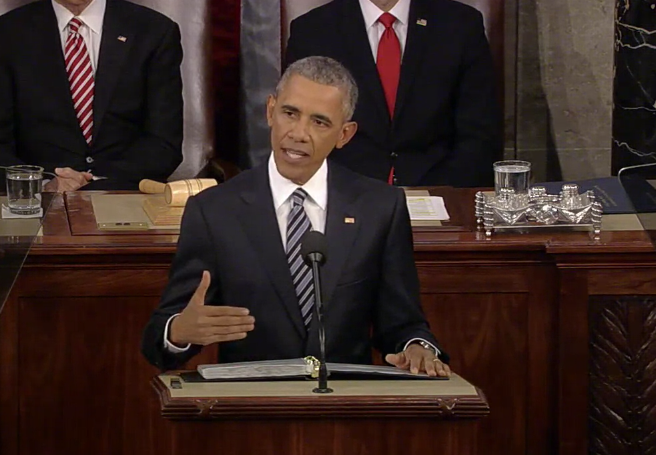

In his final State of the Union address, President Barack Obama took a sobering look at the political divide during his presidency: “It’s one of the few regrets of my presidency – that the rancor and suspicion between the parties has gotten worse instead of better.”

So, how did we get to this point? How did the president who promised hope and change wind up with gridlock and stagnation? How did the president who wanted to change the way Washington works end up with an American public that is more suspicious of D.C. than ever?

The seeds of the current political hostility were planted before Obama assumed office. Then-Senator Obama faced incendiary personal attacks first in the 2008 primary against Hillary Clinton and then in the ensuing general election.

Although it has faded from recent political memory, Clinton was not above painting Obama as “dangerous” because of his connections to Bill Ayers and his pastor, Reverend Jeremiah Wright. In short, Obama’s relationship to the two was seen to be problematic because Ayers was the former leader of a radical left-wing organization and Reverend Wright espoused views intensely critical of America. Obama condemned Wright’s views and Ayers’ crimes. Nevertheless, it didn’t stop Clinton and the majority of Republicans from attacking Obama’s character rather than the substance of his arguments. “Birtherism,” the claim that Obama was not a citizen, added fuel to the fire and only served to further the notion that Obama was “dangerous” and a shadowy figure.

In spite of all this, 2008 Republican nominee John McCain fought against those claims. A supporter at a rally said he was scared of an Obama presidency, but McCain said, “He is a decent person and a person that you do not have to be scared of as president of the United States.” The McCain campaign investigated the “birther” claims and deemed them to be false. McCain didn’t back away from bringing up Ayers in his campaign, but the Republican base didn’t think McCain went far enough.

Republicans ended up not only losing the presidency, but they also lost their majorities in the House of Representatives and Senate for the second consecutive election. Obama won in a near-landslide and deemed he earned a mandate for the policies he promoted in his campaign to become law.

Perhaps he was right that his victory was a mandate for change, but he pushed his policies down strict party lines. His biggest accomplishment, the Affordable Care Act, was passed through parliamentary tricks and without a single Republican vote. Sometimes that’s what needs to be done in order to bring about real change and Republicans aren’t without blame. However, doing so has political consequences and creates distrust between the two parties.

The Affordable Care Act became a source of major political strife. Obama signed it into law nine months before the 2010 election and every Republican vowed to repeal and replace Obamacare. On the back of their disgruntled base, the Republicans rode the Tea Party wave and ushered in many new, fresh faces into Washington. Tea Party heroes like Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz arrived in D.C. for the first time. Then-Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell pledged to make Obama a “one-term president.”

The 2010 election pushed Republicans further to the right and it became politically impossible to work with Obama on anything. Governor Chris Christie was chided in some circles for giving Obama a hug when he visited New Jersey in the wake of Hurricane Sandy. There may have been political leeway to work together in the first two years of Obama’s presidency, but both parties took actions that made it a near-impossibility to work together in the future.

The far-right began to sprout up in the 2008 elections. They made their voice heard in 2010 and then beat the Democrats in a massive landslide in the 2014 midterms. Now, they are fueling candidates like Donald Trump and Ted Cruz to fight the establishment politicians. They’ve grown louder and more numerous since President Obama’s election and there is no sign of the noise dying down.

We’ve gotten to the point where making enemies of the opposing party is encouraged and rewarded. In the first Democratic debate, Hillary Clinton said the enemies she was the most proud of making were Republicans and she got massive applause. Political opponents are seen as enemies instead of colleagues with whom to work out compromises.

Outside of the political atmosphere, the actual system exacerbates this problem. Gerrymandering, or drawing district lines to ensure a district has a large majority of one party, forces politicians to appeal to the extremes of the party and not consider the opposing party’s views. Democrats, who complain about gridlock and Republicans’ unwillingness to compromise, don’t show up to vote in midterms and allow the Republicans they disagree with the most to stay in office.

In order to change the institutional incentives for partisanship, we have to reform gerrymandering and Americans need to vote to make their voices heard.

However, that’s simply not enough. If we are serious about changing the political climate, we have to listen to our political opponents. For their part, Democrats do seem to work more with their opponents compared to their Republican counterparts, but Democrats have to realize that Republicans have ideas worth listening to and, despite what they might have heard, there are bunch of reasonable Republicans on Fox News. Republicans have to realize that Democrats are not all hardcore leftist ideologues that despise capitalism.

Truth be told, we won’t know the long-lasting impacts of this political atmosphere for another decade or two and political discord has been a staple of American politics since its inception. However, we can start fixing this by going back to debating policy based on substance rather than resorting to personal attacks. At the very least, we can genuinely listen to people who may not agree with us politically.

I won’t be holding my breath, though.