October brings a vibrant change in the seasons, welcoming a wide range of celebrations, from Halloween to Hispanic Heritage Month. Yet, one celebration often gets overshadowed: Polish American Heritage Month.

If it’s not already clear from my last name, Guziejewski (pronounced Ga-jeff-ski or Ga-jess-ski), I’m part Polish and it’s a big part of my identity simply because it’s the first thing people recognize when they see my name. Because of this it supersedes my Lithuanian and Italian identities and has come to shape who I am.

In 1981, then President Ronald Reagan designated the month of October to be dedicated to recognize the contributions Polish Americans have made to the United States. Unfortunately, since the Reagan and Bush administrations, it has been acknowledged only once, by President Clinton in 1996, before fading from the public eye.

Like all the immigration populations found here today, Polish history is deeply woven into the story of America. The first Polish immigrants arrived at Jamestown in 1608, twelve years before the Pilgrims arrived in Massachusetts. While many know the tale of the Pilgrims, the struggles and stories of the Polish immigrants who came before them are less familiar.

Brought to the colonies as indentured servants by the Virginia Company, these skilled workers played a crucial role in the colony’s economy. However, like many groups that immigrated to America, they were denied the right of representation.

The Virginia House of Burgesses instituted a representative form of government in June of 1619, which gave the right to vote only to men of English descent. In response the Poles and other Eastern Europeans organized what is believed to be the first labor strike on American soil, eventually winning the right to have their voices heard.

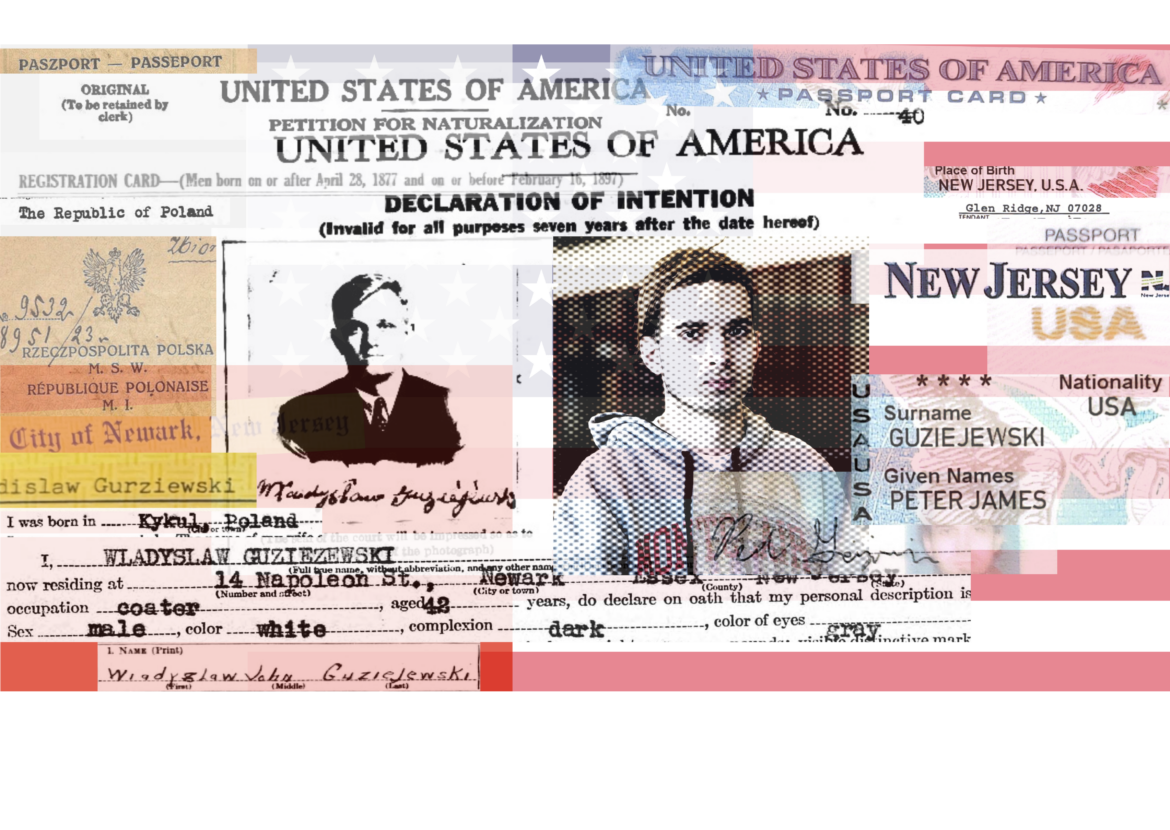

My family’s story mirrors that of many Poles who came to the States. My great-grandfather, Waldyslaw Guziejewski, later Americanized to Walter, arrived in 1907 and settled in Newark where he worked manual jobs and raised my grandfather, Stanislaw, later Stanley, and his siblings. My grandfather would go on to serve his country in World War II in many capacities but ultimately his Polish identity and language skills would lead him to interrogate suspected Nazis posing as Polish POWs.

Yet as time passed, my family began to lose their Polish identity, as immigrants often found it necessary to shed their ethnic identities to become more “American” Names like Guziejewski or Wladyslaw were shortened due to the challenges of spelling and pronunciation to avoid judgment from being “different.”

The family doctor, who was also Polish, suggested my grandfather shorten our last name to Guzik, warning that having a very ethnically Polish last name wouldn’t benefit his children. Had my grandfather followed that advice, we would have lost our outward Polish identity in just three generations.

This month is an opportunity to share stories like these about the resilient spirit of Polish Americans and to encourage those of Polish heritage to explore their own families’ journeys that shaped their identities.

The 19th century saw a wave of Polish immigrants seeking the American dream, settling in states like Illinois, Michigan as well as right here in New Jersey, making their home Newark like my great grandparents did. Many initially clustered in urban areas, but as they dispersed, so too did their cultural heritage.

Towns like Wallington have maintained a vibrant Polish community with over 50% of residents identifying as Polish. This area boasts numerous Polish restaurants, cultural events, and even a visit from Poland’s president Andrzej Duda.

Communities like these serve to enrich the cultural tapestry of the United States. But despite their significant contributions, the Poles often remain unrecognized, much like a lot of other cultural groups. The only acknowledgment I typically see comes from my credit union, the Polish & Slavic Federal Credit Union, which celebrates the month with an email. Perhaps I see one parade for General Casimir Pulaski, the “Father of the American Cavalry during the Revolutionary War, in a Polish neighborhood here in North Jersey.

Like many ethnic groups, the Poles have been fighting for America since it declared its independence, even as generations spend their entire lives in their adopted homeland.

General Pulaski Memorial Day, which also falls in October, does receive a bit more recognition. While this focus on Pulaski is well deserved, it highlights only one individual rather than celebrating the broader achievements of the entire Polish American community.

Despite the lack of recognition, the story of Poles in America has been one of great triumph. The most remarkable aspect of my family’s story is how, like many Polish immigrants, we transformed our lives in just three generations. Starting out in military and factory jobs, we have evolved into successful professionals which include doctors, lawyers and prosecutors.

As we celebrate this Polish American Heritage Month, let’s take a moment to honor the achievements and adversities that define the Polish American community and recognize the importance of celebrating cultural heritage and history. While this month may not receive widespread recognition, its significance is profound nonetheless.

For many immigrants, the push to assimilate was viewed positively, though today the conversation has shifted. While there is still a tendency sometimes for immigrants to Americanize their identities now, I believe that retaining one’s heritage should be viewed as a strength rather than a burden. It acts as both a tribute to our family’s legacies and ensures our stories remain integral to the American story.