Illustration by Camila Garcia

The government calls it protection. Students call it control. It is time for universities to decide which side of safety they stand on.

Safety has always been a comforting idea. It’s what parents promise their children, what schools pledge to their students and what governments claim to guarantee their citizens. But in today’s world, safety has taken on a different meaning — one rooted not in comfort, but control.

A 2023 study by The Guardian revealed that Google handed over data to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), giving the agency access to personal information through surveillance contracts and data requests. What was once the promise of “protection” has quietly turned into the permission to probe and stalk.

When companies — and even universities — hand over information this easily, it’s worth asking: who is actually being protected and at what cost?

The government defines safety as surveillance — collecting data, tracking movement and identifying “risks.” But students define safety differently. We define it as freedom: to learn, speak and exist without fear that our personal information will be used against us.

When protection translates into invasion, privacy is no longer a right: it becomes a privilege granted only to those deemed “safe” enough to deserve it.

The U.S. Constitution’s Fourth Amendment guarantees citizens the right to be secure against unreasonable searches and seizures. Today, digital surveillance has blurred that line. The technology that allows ICE to monitor people’s location, search history and social-media activity exists under the same justification of “public safety” that’s supposed to keep us secure.

Public safety at the expense of personal privacy isn’t safe at all; it’s surveillance with better branding.

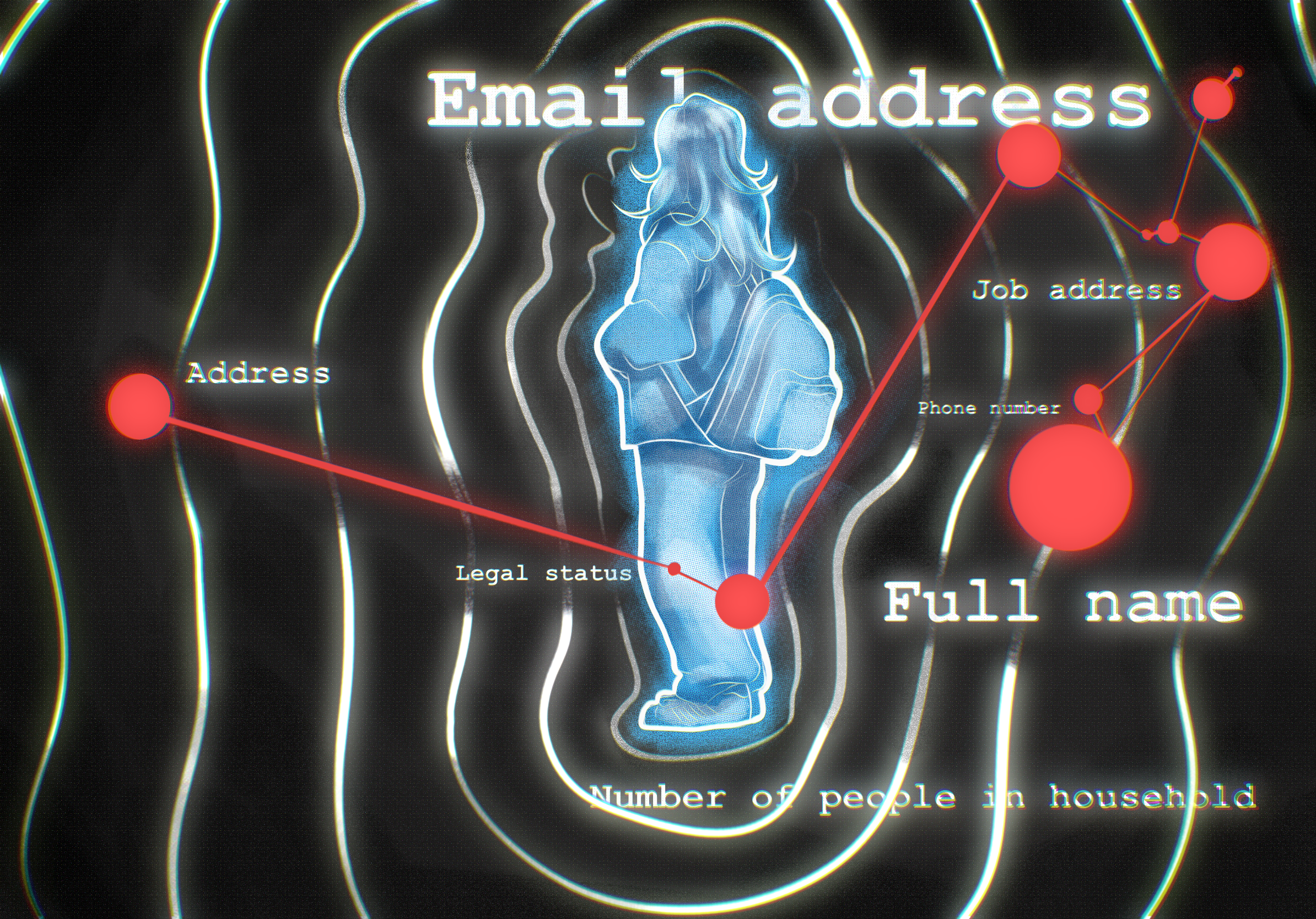

Many public colleges, including those in New Jersey, store massive amounts of student data: addresses, financial records, immigration status, class schedules and more. Under certain conditions, that data can be shared with law enforcement or federal agencies.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), was designed to protect students’ privacy. But there’s a catch: universities can release “personally identifiable information” without consent during emergencies or investigations. These loopholes leave students vulnerable – especially undocumented or international students who are now more open to being tracked and targeted.

At Montclair State University, FERPA policies explicitly state that records will not be disclosed without written consent, except under certain legal conditions. The university’s Data Classification and Handling Policy outlines how sensitive information is managed, stating it will be shared externally only when required by law. While this sounds reassuring, there is no publicly-available policy explicitly confirming that Montclair State, or any NJ public university, refuses data requests from ICE.

That silence matters. It doesn’t mean Montclair State shares student data with immigration officials — but it also doesn’t mean it never could. The lack of transparency and clarity is the problem. When “safety” depends on interpretation, trust begins eroding.

Universities are supposed to be sanctuaries for learning — places where criticism is encouraged. When students feel watched, they stop being open. They self-censor, edit their thoughts, and question who might be reading their emails or tracking their logins. Learning turns into a performance.

For many undocumented or immigrant students, this fear isn’t hypothetical, it’s their lived reality. The possibility of their own college handing over records, even legally, breaks the bond of trust that education relies on. Universities should be the buffer between students and power, not the bridge that connects them.

New Jersey doesn’t currently have state-level restrictions preventing universities from cooperating with ICE. Public institutions follow federal law, which means FERPA governs their data-sharing practices. While FERPA requires written consent for most disclosures, it allows exceptions for “law enforcement purposes.” So, schools could comply with federal requests without notifying students.

In 2017, some New Jersey universities — including Rutgers — faced pressure from student groups to declare themselves “sanctuary campuses,” promising not to share immigration data unless legally compelled. But many schools stopped short of full commitments, citing federal funding risks. That hesitation exposes the tension between moral responsibility and legal obligation.

If universities want to protect students, they should move past compliance and embrace transparency. Posting clear, accessible policies and alerting affected individuals isn’t radical; it’s an exigent provision.

Students deserve to know when and why their data might be shared. Colleges love to talk about empowerment, but empowerment starts with information.

We can’t control how the government defines safety, but we can drive how our schools practice it. We should demand for public disclosure of data-sharing policies, join campus privacy advocacy groups and use digital-security tools that minimize personal tracking.

Protecting students means protecting the university — its ideas, growth and voices. Compromising that trust in the name of “protection” means they stop being protectors and start being participants in the very systems students fear.

True safety isn’t found in surveillance or data logs. It’s found in trust — the kind that can’t be tracked, sold or surrendered.