The favela: the type of Brazilian slum that exists in hundreds of municipalities throughout the country. It is symbolic to Brazil, entire neighborhoods that are brutalized and neglected, yet often romanticized by the foreigners who feel the need to visit.

The favelas are the backdrop of the socioeconomic issues that Brazil faces. Many are controlled by drug traffickers, experience immense police brutality and receive little economic assistance from the government.

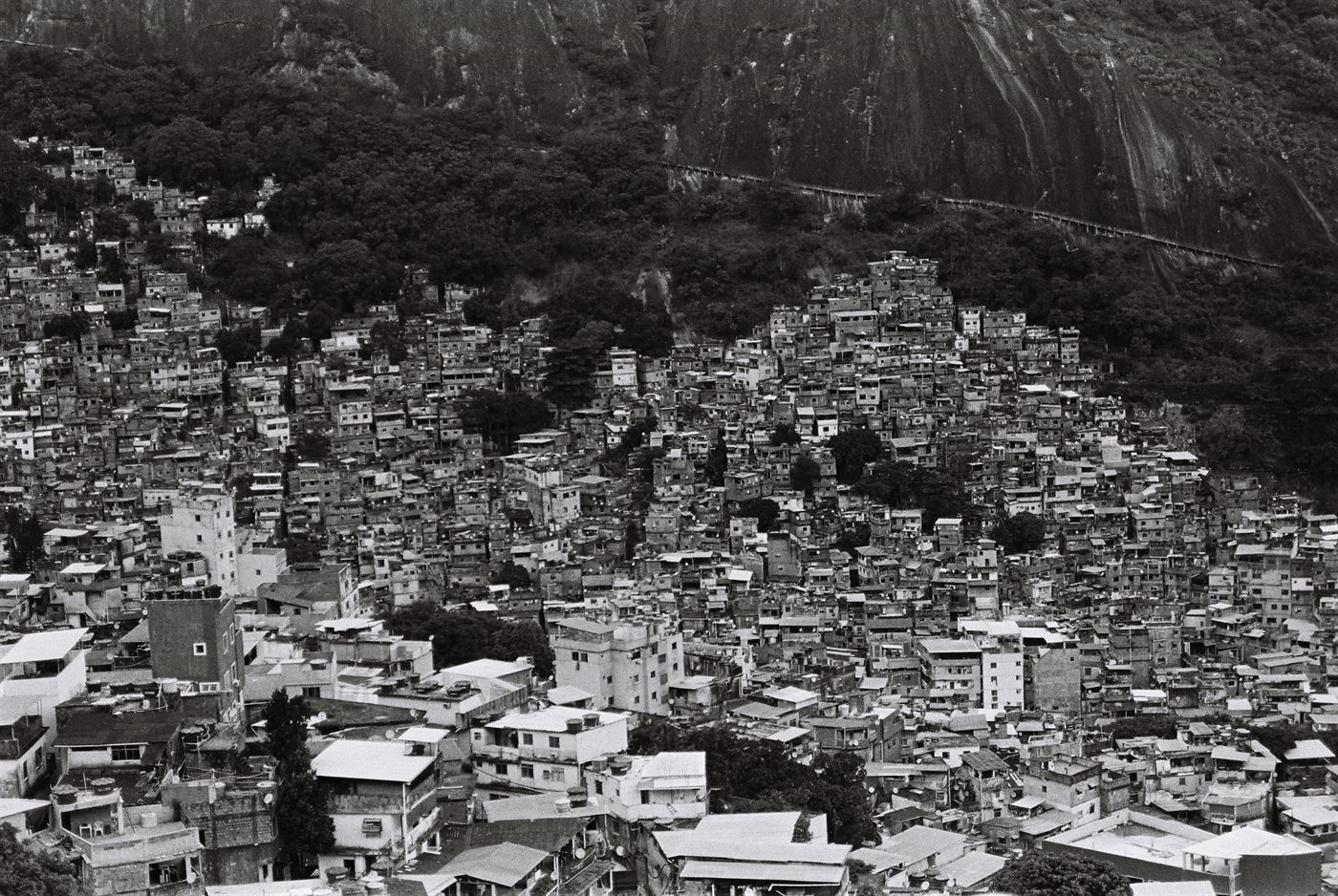

A partial view of Rocinha from one of many “lajes” — literally meaning “slab” in Portuguese, but means a viewpoint.

Julian Rigg | The Montclarion

It had been eight years since I last spent time in Brazil. My trip back had begun as a simple family visit to Rio de Janeiro, but my itch to photograph and connect with my fellow countrymen had not yet been scratched.

My eyes were locked on Brazil’s most famous favela: Rocinha. With over 180,000 residents, Rocinha is by far the largest favela in Rio de Janeiro and Brazil — let alone one of the largest in South America.

I contacted a mutual friend named Maycon, who I was introduced to by Brazilian photographer and friend André Cypriano. Cypriano had extensively photographed Rocinha for years; my two days paled in comparison to the work of Cypriano.

Maycon is a 32-year-old motorcycle taxi driver in Rocinha, a rewarding profession considering it is the most widely used mode of transportation in the favela. He was born and raised in the favela; he is a man that knew his neighborhood and the people as if they were his own family.

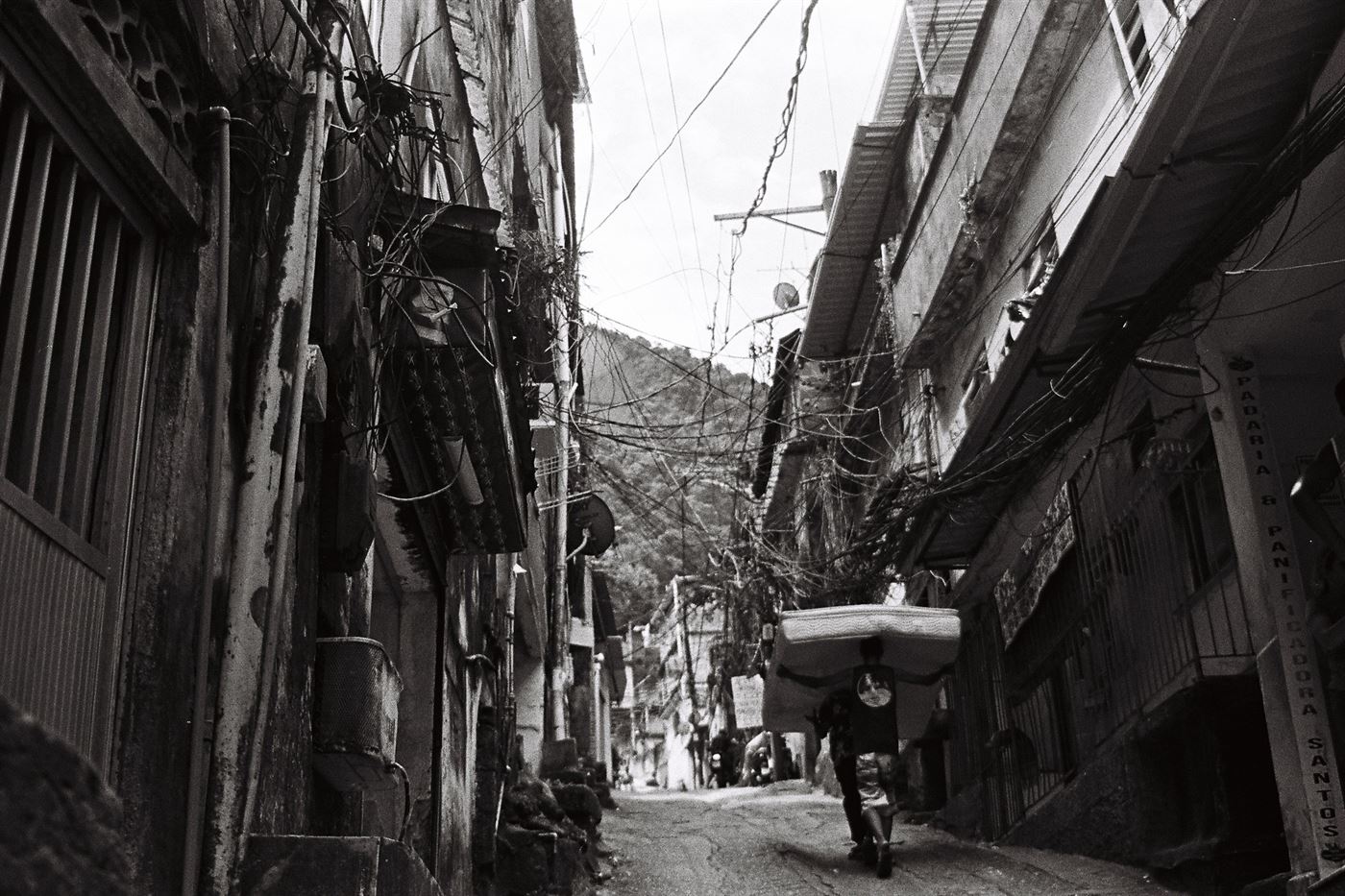

A woman leans on a motorcycle while looking off into the “beco” — the Portuguese word for “alley.” Rocinha is filled with narrow, yet incredibly long becos. Most becos are named or numbered.

Julian Rigg | The Montclarion

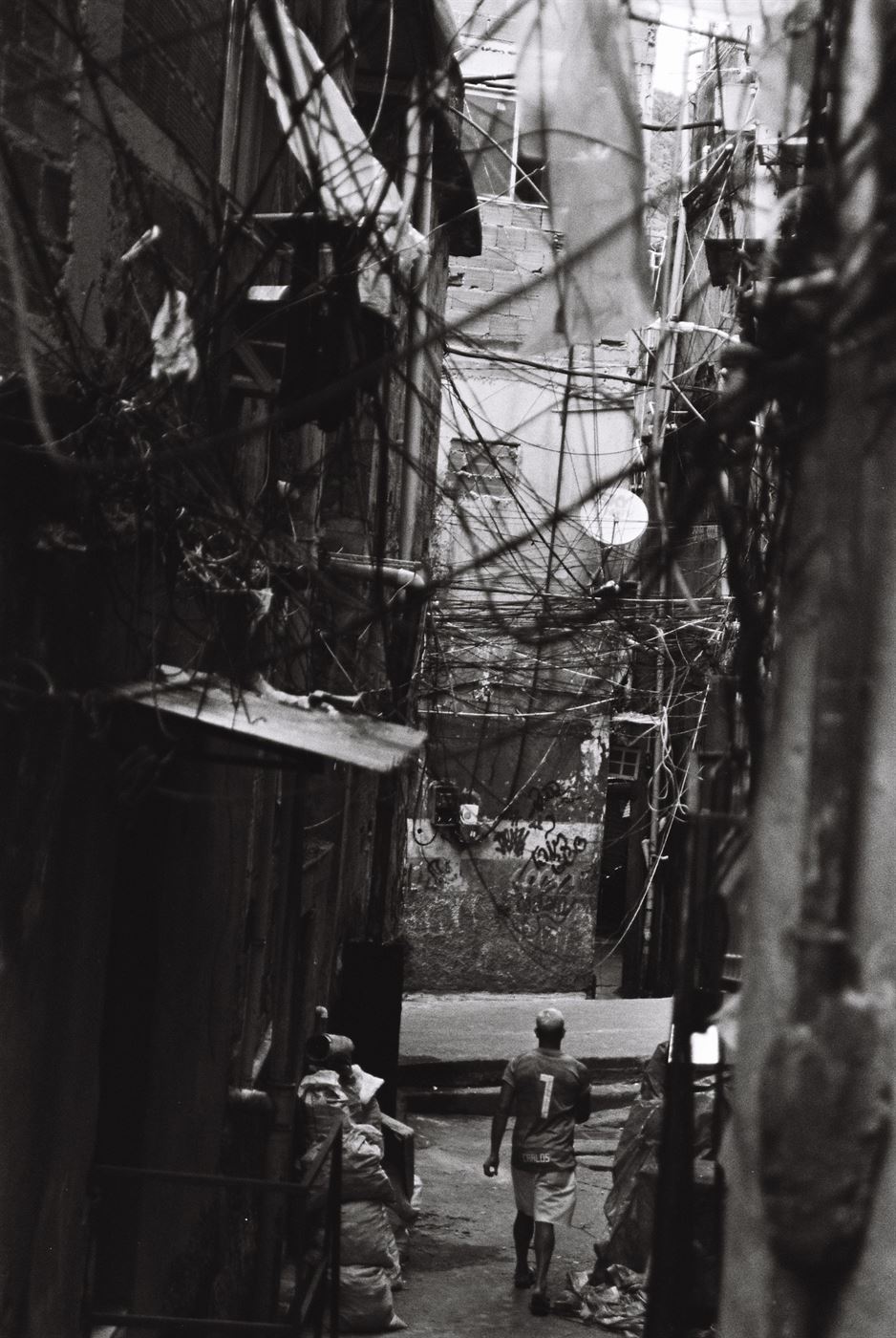

A man walks through a beco. His hair is bleached, a tradition amongst Brazilian men to partake in around New Year’s.

Julian Rigg | The Montclarion

I met with him on a Wednesday morning in early January. Rio de Janeiro had been coming down from the prior New Year’s celebrations and was beginning to find its stepping once again. Armed with my old Nikon and several rolls of black and white film, I was equipped for my trip inside.

I shook Maycon’s hand and hauled myself onto the back of his motorcycle.

We danced through the morning rush traffic, dodging past idle cars, delivery trucks and the occasional family on-foot running their morning errands.

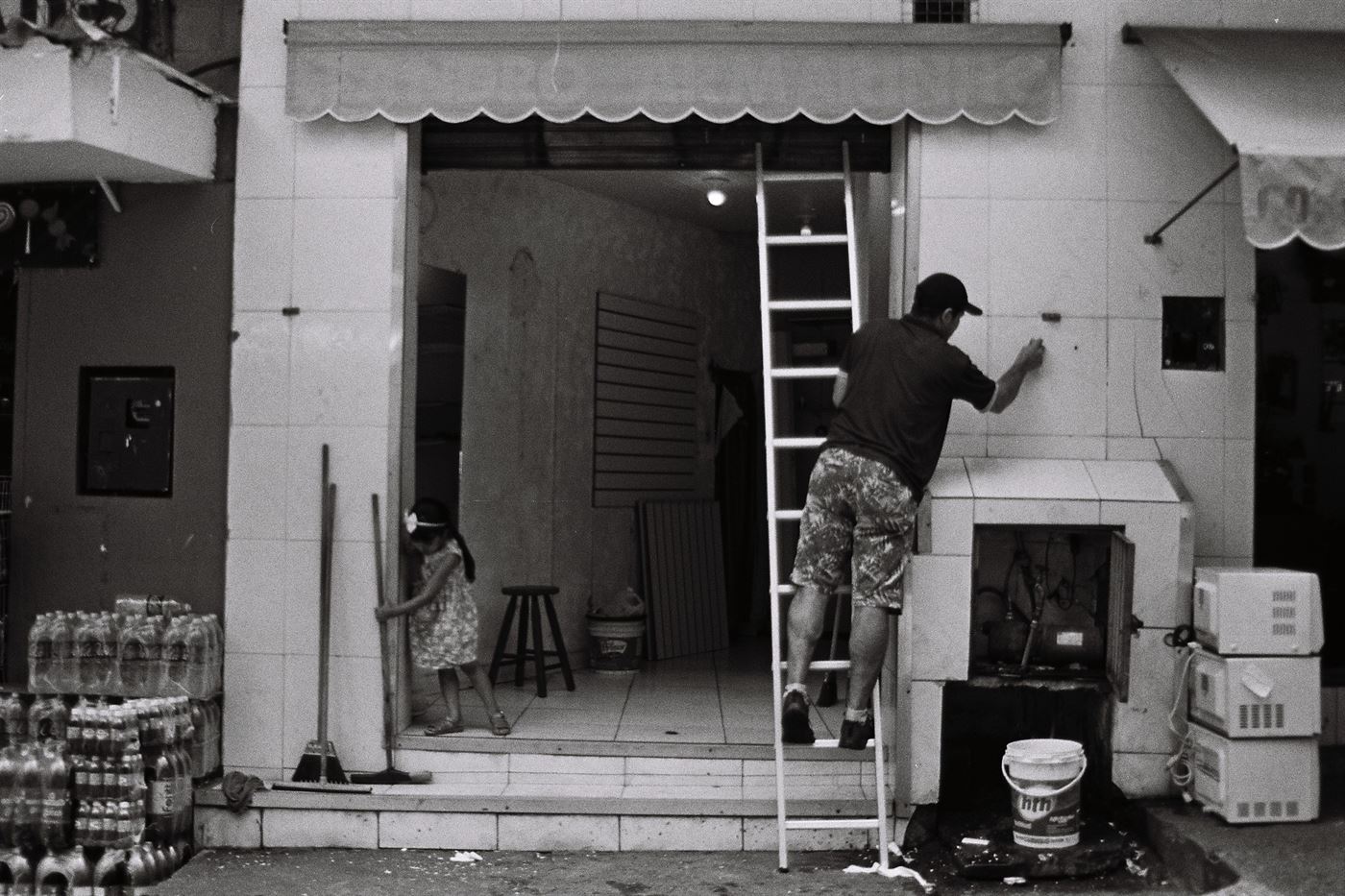

A mother and her children walking down one of Rocinha’s main avenues. Rocinha has several main streets where most businesses are located.

Julian Rigg | The Montclarion

Maycon brought me to one of the iconic viewpoints of Rocinha, a look down the valley where the neighborhood had been built over several decades.

“Three years ago, it was really bad,” Maycon had been telling me. “It was war.”

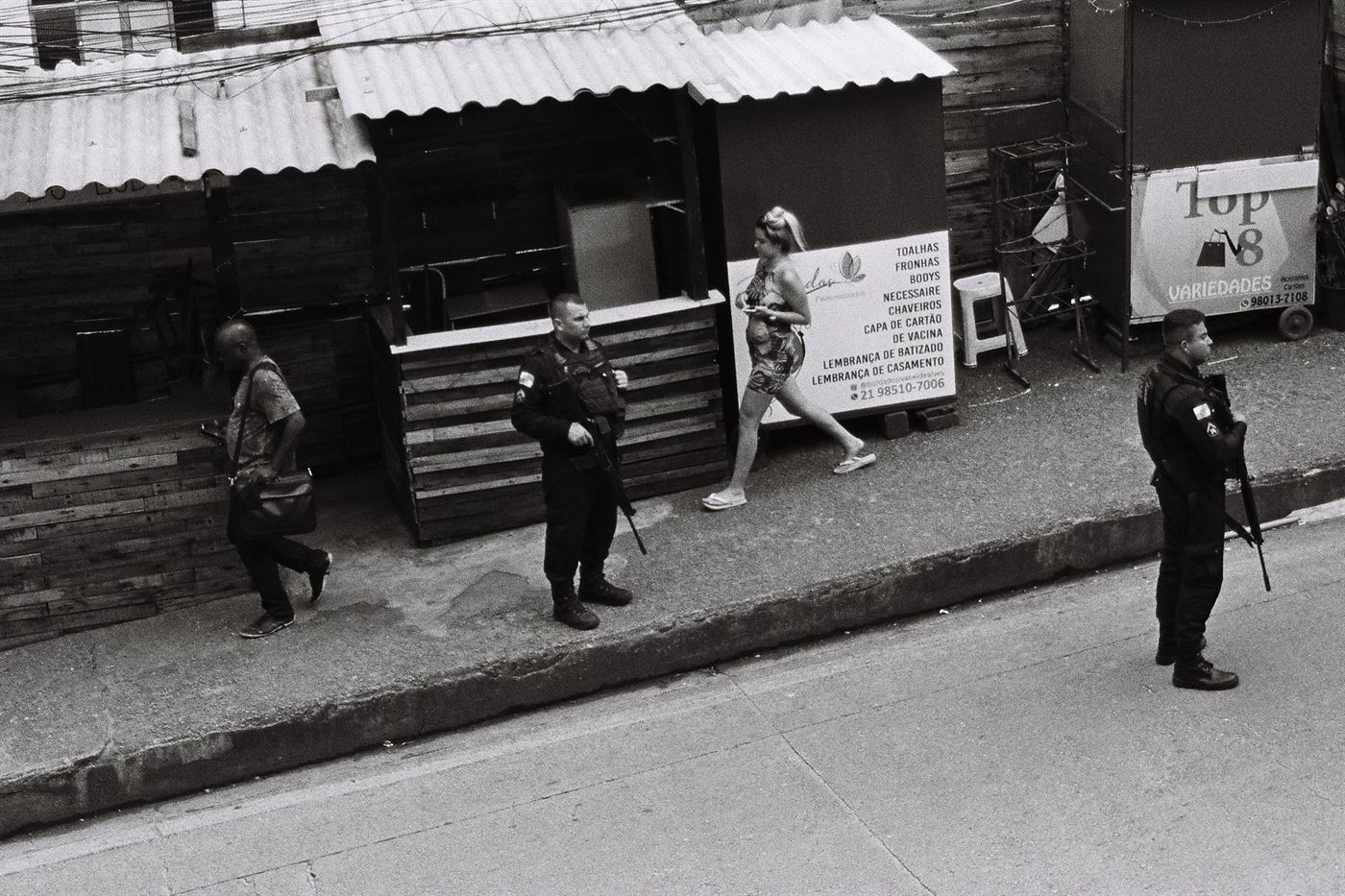

Rio’s military police conduct what is known as a “blitz” — random traffic stops with the goal of finding known drug traffickers.

Julian Rigg | The Montclarion

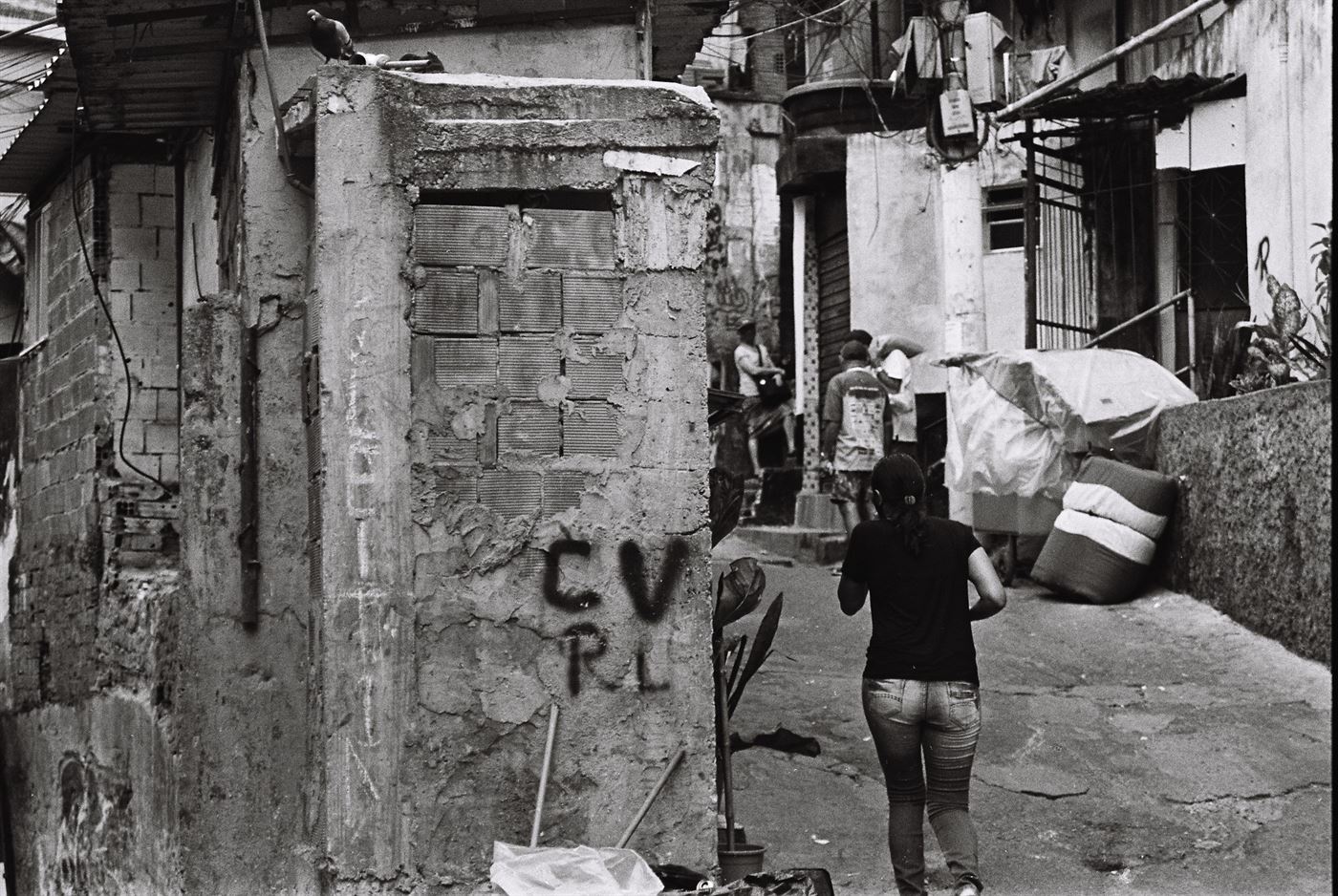

Maycon was referring to the turf war between the Amigos dos Amigos (ADA) and the Comando Vermelho (CV), two of Brazil’s largest drug trafficking organizations.

Over the course of two days, Maycon led me through the streets and alleyways of Rocinha. It was a constant game of whether or not I could photograph; the favela is currently under the control of the Comando Vermelho who had taken back the neighborhood during the turf war three years ago.

A city-employed street sweeper pushes a trash bin down Estrada da Gávea.

Julian Rigg | The Montclarion

Our trek took an ultimate turn when Maycon told me to simply put my camera away in my bag — a stark contrast to the simple “just put it down for now.” This was after a young man came out of nowhere, telling us that I “shouldn’t even have a camera.”

We turned a corner finding ourselves along a road with several shops conducting businesses to our right. To our left, lining the white walls of the street were dozens of shirtless men sitting on plastic lawn chairs, large assault rifles resting on their laps.

One of the armed men — most likely a commander — donned a massive gold chain, with a diaper-clad monkey on a leash seated on his shoulder. Without a doubt, these were the men of Comando Vermelho.

Coming off the open road we had just walked down, we began our way past a bar, where two young men were watching a soccer game, AK-47s resting on their laps.

“Hey! Maycon! What’s up?” one of them had yelled out to Maycon. It was a friend he had grown up with in school. I shook their hands, exchanging names and prazer, a way of telling someone it is a pleasure to meet them in Portuguese.

I’m not going to be able to explain the issues that Brazil has in this short article or in my photos; it is a beautifully complicated country with titanic issues. Two days in Rocinha is not nearly enough to even convey what is important to convey.

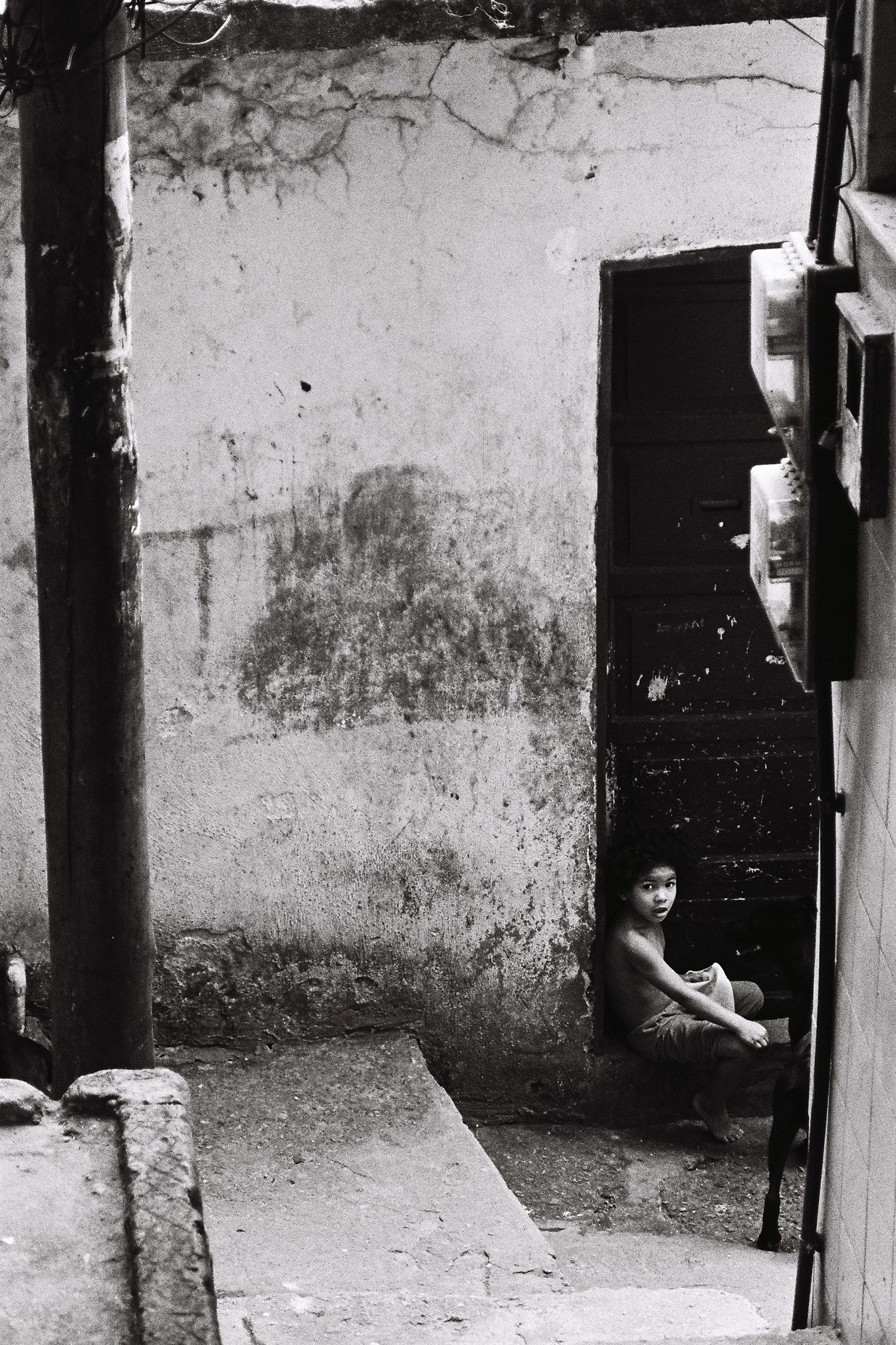

A man named Eduardo stands in the doorway of a local corner store located in one of Rocinha’s many becos.

Julian Rigg | The Montclarion

What I can say is, however, I received a slice of life inside of Rocinha. A slice of life that I hope shows that Brazil is far more than just soccer and samba. It is a country filled with hopes and dreams; one that craves a future free of corruption, violence, scandals and pain. I have faith.

My photos from Rocinha will be on display at Ridgewood Coffee Company in Ridgewood, New Jersey throughout the entire month of March.

Graffiti of the initials “CV,” which stands for “Comando Vermelho” — or “Red Command” in English. CV is the oldest and one of the largest criminal organizations in Brazil.

Julian Rigg | The Montclarion

A boy leans against a wall with sneakers dangling from power lines in front of him. He can be seen wearing a Flamengo jersey — the main kit of Brazil’s most popular soccer club.

Julian Rigg | The Montclarion