“Sorry, everything’s been so crazy, we’ve been renovating our house,” Shakoure Charpentier said as he walked into his small home office. But for someone who was just released from a detention facility the other day, home renovations were not an expected concern.

Journey deep into the F Line on the New York City subway, stop by a local bodega on the way and head a little east past Jamaica, Queens, and you will find the quiet neighborhood Charpentier calls home.

He is a peaceful person; a man of faith and family whose gentle voice can be heard clearly over the sounds of “A Tribe Called Quest” playing in the background. He speaks of his drive, passion and determination to create and to change. However, it is put on hold when he recalls what happened on July 6, 2020.

“My wife, she was getting ready to go to work,” Charpentier said. “She was at Lenox Hill Hospital in the city. You know… you can probably understand watching your mother cry or your daughter cry, or your wife cry as they take you away in handcuffs. That’s… That’s the worst thing.”

That morning, eight agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement, more commonly known as ICE, showed up at Charpentier’s home unannounced. His wife Nathalie answered the door.

“They wanted to ask a couple of questions they [had] for me,” Charpentier said. “I came downstairs and that’s when they dropped it on me.”

Shakoure was taken to the Bergen County Jail in Hackensack, New Jersey, one of several NJ jails with ICE contracts.

What he thought to be something that would only last seven days ended up lasting seven months.

Shakoure recalls that he became “physically sick” while inside due to his mental health. By the end of his time there, he had told a close friend during a phone call that he was “clinically depressed.”

This was primarily due to the nature of the Bergen County Jail: a facility that was not designed to house people for months on end.

“A week or two, I understand,” Charpentier said. “But you can’t just put a person’s life on pause for months on end and not give them anything to engage in.”

Charpentier paused, a clear indication of the difficulty of his experience. He shook his head and said they would just sit around all day and do nothing. To add insult to injury, Charpentier even considered joining the hunger strike that was happening at the time, which was started in protest of the jail’s conditions and ICE’s policies.

The only thing that saved him was the telephone, a small portal to the outside world where he could speak to those he cared about for a brief 20 minutes.

But when looking at Charpentier’s situation, it becomes stranger with a key detail: he is a U.S. citizen.

So why was a community activist, filmmaker, entrepreneur and U.S. citizen being held under ICE custody?

According to Charpentier’s attorney, immigration lawyer Julie Goldberg, Charpentier was presumed to be targeted by one of many “denaturalization programs” that began under the Obama administration, seeking out those who became naturalized citizens but have criminal records. These programs target those from “countries of interest,” which Goldberg says means “those of color and Muslim faith.”

Goldberg says the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees ICE, withheld documents proving Charpentier’s citizenship, which she says was a “cover-up.”

In fact, Charpentier was actually born on a U.S. Air Force base in Germany in the late 1970s. His father was a Haitian immigrant but had U.S. citizenship along with his mother. At the age of two months, Charpentier moved to New York City but was threatened with deportation to Haiti because of said denaturalization programs, a country he has never been to.

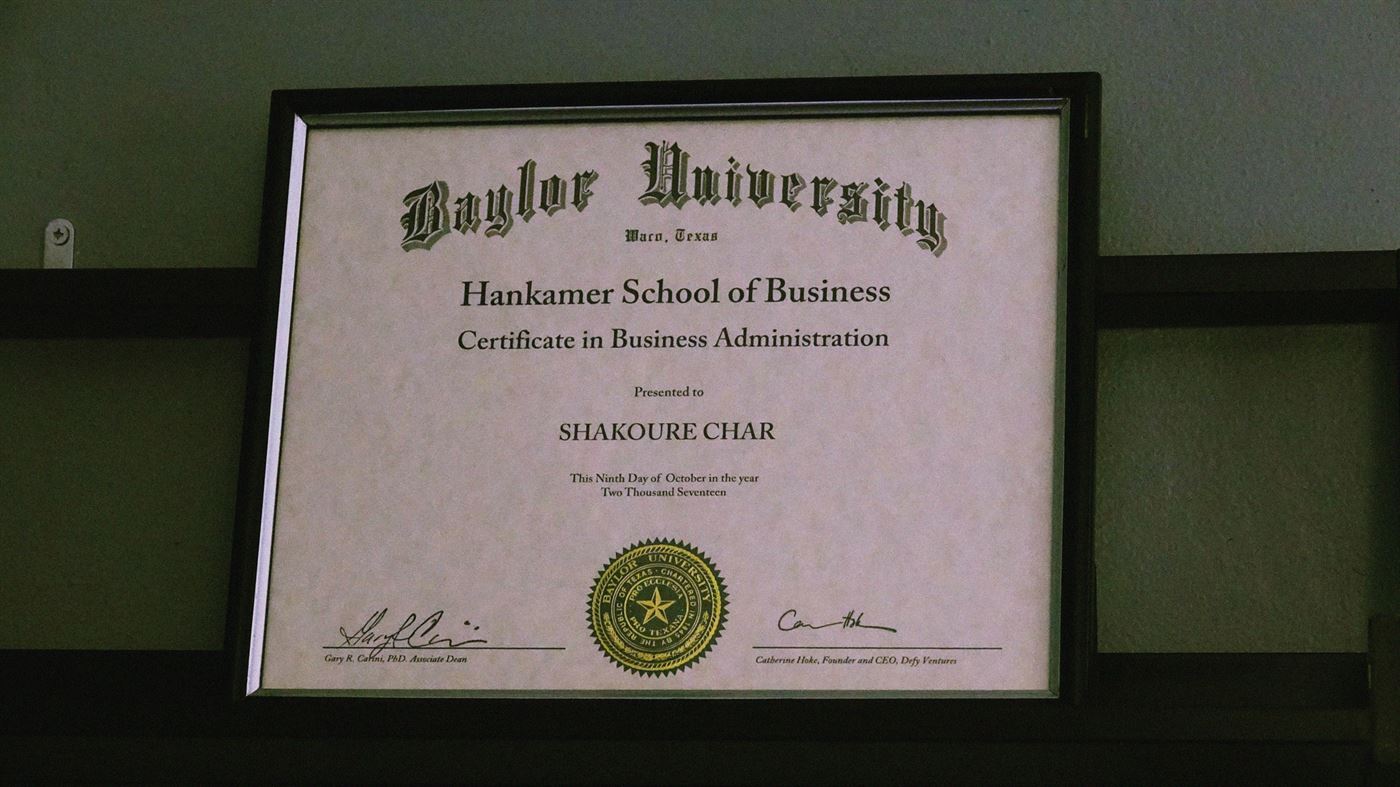

One of Charpentier’s three degrees, all of which were completed in his 24 years of incarceration.

Julian Rigg | The Montclarion

The criminal record that resulted in Shakoure’s ICE arrest was a joyriding charge from when he borrowed his friend’s car at the age of 18; a car which his friend did not tell him was stolen. He was charged with an aggravated felony, which prevented him from fighting his case outside of Bergen County Jail.

Shakoure also had another charge that went ignored by ICE, a key part of his record that could have changed the entire situation.

Shakoure was previously incarcerated for 24 years for being “guilty by association” for a 1990s New York City subway murder he did not even see occur. It came a year after the events of the Central Park Five, even being investigated by the same detective on that very case.

“Like I said everything you’ve worked towards family, home, business, non-profit; you put your life in that,” Charpentier said. “So for someone to come along and say ‘yo, that don’t mean anything, we don’t care about that. We locking you down and potentially casting you out of the country.’ How do you process that?”

He credits his release to the work of Goldberg, as well as an army of activists and a following on the app TikTok, where “#FreeShakoure” has been viewed over 161 thousand times.

Now, Shakoure wears an ankle tag, tracking his every move.

Despite this, he seems at peace being home with his stepchildren and wife. He sits in the new office planning his next moves, pointing out that his office was downstairs just several days prior.

He looks back at his accomplishments fondly, smiling under his baby blue surgical mask. During his 24-year incarceration, Shakoure completed two bachelor’s degrees, a master’s degree, joined a theater company and became a quarterfinalist in an international screenwriting competition while also reading well over 500 books.

For now, he focuses on his 3D media company, Transcendence Media, as well as his nonprofit From Bars II Beyond, which helps young people affected by the criminal justice system learn marketable skills.

Shakoure looks toward the future cautiously.

“I don’t want to even have to show up for my court date,” Charpentier said, counting on the judge simply throwing out his case.

But in the meantime, he sits and hopes; hopes that one day ICE will leave him alone.