Over the summer with the news of the Titanic submersible disappearing, we saw the media suddenly shifting back its usual reporting a month later, almost as if it was a stand-alone episode of an event.

Some stations appeared even to become “self-aware,” starting to critique and comment on how the “media” whipped their heads around and stared at this event unfolding, when the rest of the world was going about with their lives.

In my email inbox, I got one National Geographic op-ed article along the lines of “How tourism is ruining the ocean and such.” A day later, I got another article email about James Cameron’s reflection on the issue and his experience with a submersible to create the movie “Titanic.” You could say there is an “arts-creativity-authenticity” argument to justify his trip.

However, I would like to mention that there is a reason that real scientific researchers, not tourism researchers, have created unmanned vehicles to go to such depths of the ocean, including to get shots of the Titanic, recording many hours of underwater footage to study later. If the footage is sufficient for scientific research, is it not enough for movie inspiration?

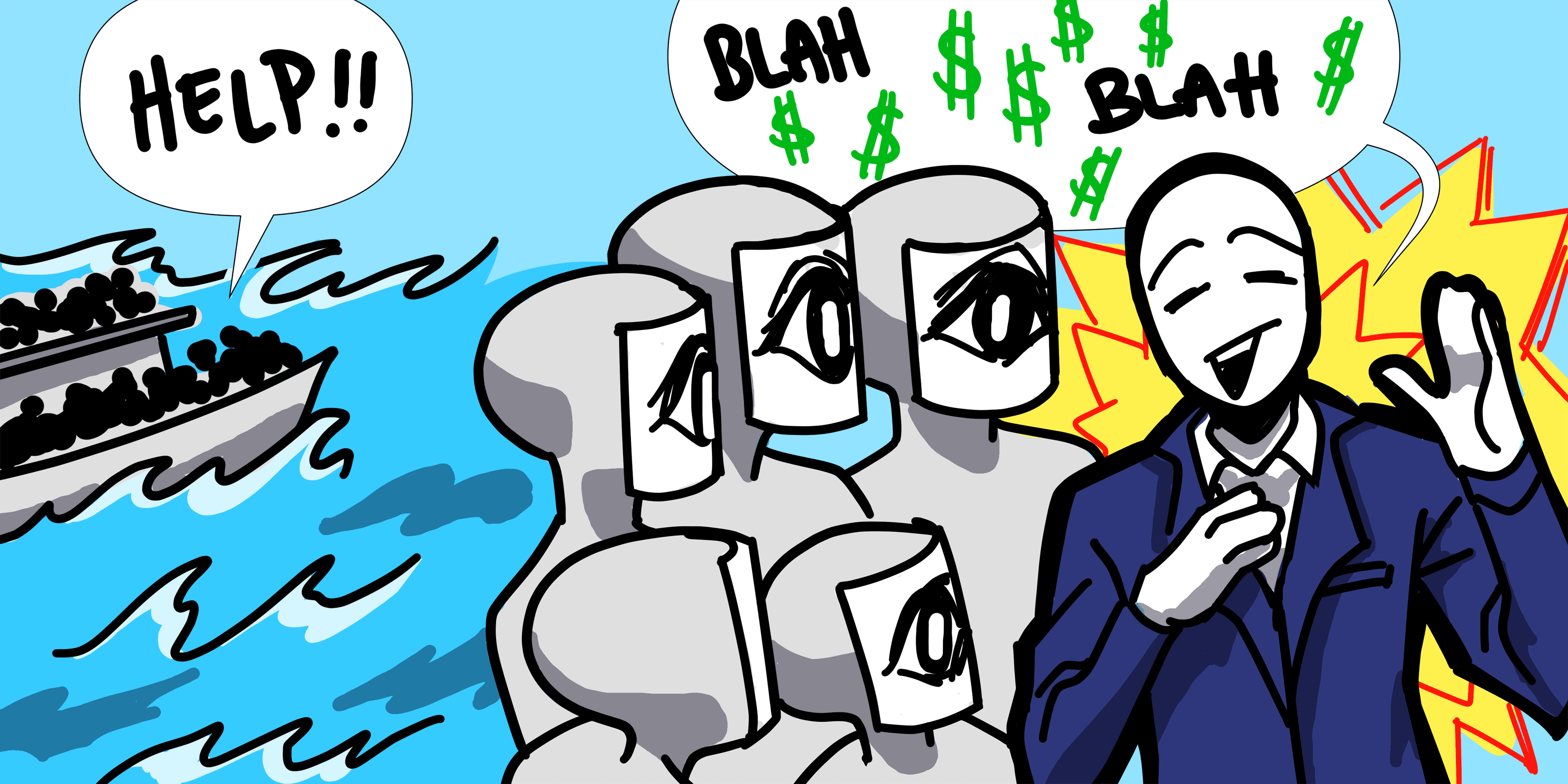

Going back to the media’s coverage, the purpose of the news is for citizens to be informed of what’s happening around them, locally and internationally. We want to know how and why the things occurring might affect us.

What we find is that the platforms that are supposedly tailored for everyday, relevant citizen consumption are somehow swayed and overridden by influences larger than us.

I am not saying the media is inherently tied to these “larger” forces. But we see time and time again how rich people, with little connection or interference, take up screen time out of the blue. How does their activity even affect society?

Sometimes it is our perception of how they “do” or “may” influence our lives. In turn, we inadvertently make them relevant in our lives by engaging with news and talking about them, when they really have no ties to us in the first place. Maybe it’s because there are so few of them that we are intrigued. Or, maybe it’s how their resources allow them to be louder, more prominent and greatly advertised.

For clarification, labeling or denouncing this as the result of a Marxist, bourgeois-proletariat struggle does not clear up the haze that “news” clouded us in for the month of June. The submersible is one solid example of how something obscure and random captured our attention in a frenzy we could not explain but went along with nonetheless.

Now, we nearly forgot that it happened. And yet, it felt so important and distressing at the time. I assumed some kind of new regulation for submersibles would be put in place. That is until I realized that such trips are not accessible to most people, and this was simply a risky, expensive luxury that concerns us in no way shape or form.

What this ultimately suggests is that we’re not relevant if we are not investing or acting out bizarre, exclusive things. It also teaches us that when these random, attention-directing things come about, we might not know why it’s important, but everyone “says” it is, so that’s that.

And perhaps this is the worst kind of news to find ourselves engulfed in.